Are you a mature but still lively Victorian brewery? Do you worry that younger breweries, with their weird American hop varieties, shiny stainless steel lauter tuns and one-off wacky recipes, are luring your customers away? Is your 150-barrel minimum brewlength too inflexible to make experimental brews on? Worry no more: install your own microbrewery on the premises, and you too can be hitting the bartops with mango-flavoured double IPAs and smoked malt saisons. Comes with clip-on manbun and removable extra-bushy beard for all brewhouse operatives …

That’s unfairly sarcastic: I have no problems at all with big brewers who respond to the craft micro-brewery challenge by bringing in their own tiny set-up: I had great fun playing with the 10-barrel mini-brewery Brains installed at its site in Cardiff. The Brains plant, like those installed at Shepherd Neame in Kent, Hook Norton in Oxfordshire and Adnams in Suffolk, is designed to brew short-run one-off beers for selling in the company’s pubs. The Caledonian brewery in Edinburgh, however, has gone for something craftily different: an on-site microbrewery that is solely for experimenting with, making brews that, should they prove to be successful, will then be scaled up for commercial production in the main brewery.

I last visited the Caledonian brewery more than a quarter of a century ago, in 1989, which was just two years after it had been the subject of a management buy-out to acquire it from Vaux, the Sunderland brewer, which had bought it in 1919. The brewery was founded by George Lorimer and Robert Clark in 1869, and Vaux took it over to supply the North East of England with Scotch Ale, a style of dark, fruity beer then very popular in the region. Edinburgh was once the third biggest brewing city in Britain, after Burton and London, and even in 1958 it has 18 surviving breweries. One upon one they closed: Vaux announced it wanted to shut the Caledonian in 1985. Fortunately for posterity, its then managing director, Dan Kane, an active Camra member, and his head brewer, Russell Sharp, felt there was enough demand for the traditional beer it made for the business to be viable on its own. In a regular irony, the lack of investment by Vaux over the years meant the Caledonian brewery still retained old-style equipment long replaced elsewhere, most notably open direct-fired coppers, which gave the brewery an excellent marketing story.

Despite a couple of fires at the brewery in the 1990s, those coppers are still there (though one is a replica, replacing a vessel lost in the fire of 1998, and they now appear to have suspended lids I don’t remember from before). Brewery manager Craig Steven says the now unique coppers give all the brewery’s beers a distinctive rotundity he always recognises in blind tastings. In 1991 the brewery launched a golden IPA using the name of another old Edinburgh operation, Deuchar’s, which had closed in 1961. That beer’s popularity was cemented with the award of the Champion Beer of Britain title by Camra in 2002, and it remains one of the UK’s best-selling cask ales. Then in 2004 the Caledonian Brewery lost its independence again, being bought by Scottish & Newcastle after S&N closed the old McEwan’s Fountainbridge brewery in Edinburgh. Just four years later the Dutch giant Heineken swooped on S&N, and Caledonian is now the second-smallest brewery (out of 165-plus) in what is currently the world’s third-largest brewing group.

Which is why, presumably, they can afford to fly me up to Edinburgh, stick me in a four-star hotel, take me out for a very fine dinner in one of the Scottish capital’s best eateries, and all so I can see the new “Wee George” microbrewery (named for George Lorimer) and try the first beer to be scaled up and rolled out after trials on Wee George, an American-style IPA called Coast to Coast. There are those beer writers who would turn down being filled full of roast venison at a brewer’s expense in the belief that it would compromise their independence: I like to claim I’m not that cheaply influenced. (That is to say, you CAN influence me, but it will cost you lots …)

Talking of independence, Caledonian’s MD, Andy Maddock, who joined the Scottish brewer in March last year after six years as a senior sales and marketing man at Heineken, says his operation has an “arm’s length” relationship with its Dutch parent, allowing it to be entrepreneurial and to follow its own path as a “modern craft brewer”. There seems to be considerable fondness for the Caledonian brewery at the top in Heineken: they like its hands-on old fashionedness, and Michel de Carvalho, husband of Charlene Heineken, who inherited the business from her father Freddie in 2002, has apparently said Deuchars is his favourite beer.

The advantages Caledonian has over most of its rivals, of course, are that as part of a huge conglomerate its financing is cheaper to arrange than a totally independent operator could manage, though it still has to have “all the rigour” in its budgets that any commercial operation has to have; and it can use its Heineken connections to get into other markets. Currently 95 per cent of sales are “domestic”, but in the next four to five years, Maddock says, he wants to see exports increasing, with Deuchars in particular and also Coast to Coast and the brewery’s new “craft lager”, Three Hop, being aimed at Western Europe. He also wants to see Caledonian’s beers making a bigger impact in the off-trade (“We haven’t punched our weight there yet,” Maddock says), and a greater awareness among drinkers that Deuchers is a Caledonian beer: it appears many Deuchars drinkers don’t actually know who makes it.

The advantages Caledonian has over most of its rivals, of course, are that as part of a huge conglomerate its financing is cheaper to arrange than a totally independent operator could manage, though it still has to have “all the rigour” in its budgets that any commercial operation has to have; and it can use its Heineken connections to get into other markets. Currently 95 per cent of sales are “domestic”, but in the next four to five years, Maddock says, he wants to see exports increasing, with Deuchars in particular and also Coast to Coast and the brewery’s new “craft lager”, Three Hop, being aimed at Western Europe. He also wants to see Caledonian’s beers making a bigger impact in the off-trade (“We haven’t punched our weight there yet,” Maddock says), and a greater awareness among drinkers that Deuchers is a Caledonian beer: it appears many Deuchars drinkers don’t actually know who makes it.

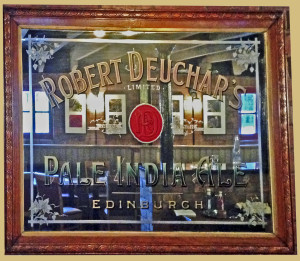

An original Deuchar’s brewery mirror, now in the tasting bar at the Caledonian brewery, rescued from a pub in Bath

On the other hand, they know why they drink it, or at least Caledonian does: “drinkability”, that mysterious characteristic no brewer knows for certain how to achieve, but which is vital for a beer to win a substantial slice of the market. Strangely, Caledonian is one of the few breweries I’ve visited where “drinkability” has been emphatically placed in the heart of the business strategy. Maddock says that the future of Caledonian will be based on a “modern” range, with beers such as Coast to Coast, that emphasises “distinctiveness and accessibility”, and a “traditional” range, led by Deuchars, where “drinkability is really important”. The idea, clearly, is that if you fancy trying one of those new craft beers, you can be reassured by the Caledonian name that it won’t be a frightening experience you’ll never want to repeat; and if you’re looking for something comfortable and more familiar, Caledonian has that for you as well. “Comfortable and familiar” are, frankly, far too under-rated among beer raters: most people most of the time don’t want to be challenged by their beer. Indeed, probably, most people don’t want to be challenged by their beer any of the time. “Predictable but not boring” is a great position for your brand to take, if you can capture it. “Predictable” also has to mean “predictably good”, of course, and part of that means making sure your raw materials are top quality: Caledonian has insisted for a long time on using what it says is the best malting barley in the world, from the east coast of Britain, both Southern Scotland and East Anglia, it also only uses whole-leaf hops, and it has now altered the way it buys hops, eschewing the traditional hessian hopsack for vacuum-packing in foil, believing this to keep the hops fresh for longer.

So to Wee George: Caledonian’s answer to the fact that there are now 100 breweries in Scotland, very few of which can match it with the popularity of its “traditional” line-up, but at least some of which offer are going to have widespread appeal – “widespread appeal” being the market sector Andy Maddock and his crew would like to own most of, thank you. It’s a £100,000 collection of hand-assembled stainless-steel kit capable of producing just 400 litres at a time, around a thirtieth of the main brewery’s capacity, but it has its own filler that can be used to put the beer into bottle, cask or keg, and it even has a hopback, just like the “big” brewery. Hopbacks are an old-fashioned item of kit today, replaced almost everywhere by whirlpools, but brewers who have kept them have realised that a hopback can be a terrific tool for adding all sorts of flavour to your hot wort. The new kit went in on June 1, and since then it has been producing one beer a week – the first being a version of Deuchar’s IPA, presumably to see how different the recipe would turn out on the Wee George kit compared to the Big George kit. Scaleablity was a problem at first, but the Caley brewers are getting better, they told me, at working out what tweaks were likely to be needed to translate a brew from Wee George to the main brewery.

The first Wee George beer to make it from experiment to scaled-up bar-top brand, Coast to Coast, was pushed through in eight weeks, which shows that for a 146-year-old, the Caley can be nimble enough when it wants to be: most big breweries barely have a meetings cycle that short, never mind the NPD pipeline. The name comes from the combination of West Coast of American hops – Simcoe, apparently – with East Coast of Britain barley. It’s a perfectly fine craft-beer-with-training-wheels, I suspect there’s an as yet untapped market for such brews among people looking for a beer to have when you’re only popping in for one and you want something with more flavour that usual but not TOO much, and I’d give it a fair chance of doing very well. Though if I were any good at predictions, I’d be much richer than I am.

Many thanks to the Caley crew for taking me north to meet Wee George, and I look forward to tasting future roll-outs.