![Black Eagle sign]()

Black Eagle sign, Brick Lane

The huge sign on the outside of the building on the corner of Hanbury Street and Brick Lane is clear enough: Truman Black Eagle Brewery. Nobody passing by could have any doubt what used to happen here, even though no beer brewing has taken place on the premises for more than 20 years. But what few people know is that for a couple of decades in the middle of the 19th century, this was the biggest brewery in the world.

Today Brick Lane, Spitalfields, in the East End of London is bustling and cosmopolitan, the heart of what is sometimes called “Banglatown”. For hundreds of years Spitalfields – filled with cheap housing, in large part because it was to the east of the City, so that the prevailing westerly winds dump all the soot from the West End over it – has been a place where poor immigrants to England come to try to scrabble a living, generally in trades connected with making clothes: Huguenot silk weavers from France fleeing Catholic oppression, Irish linen weavers fleeing unemployment in Ireland, Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in Russia, Bangladeshis fleeing poverty, all adding their tales to a place crowded with both people and history. But it wasn’t always thus: the author Daniel Defoe, who was born in 1660, remembered Brick Lane from his childhood in the early years of the Restoration as “a deep, dirty road frequented chiefly by carts fetching bricks into Whitechapel”.

Over the decade after Charles II returned to England, as London expanded, development spread up Brick Lane itself from the south, and new streets were laid out in Spitalfields where previously cows had grazed. Two of these streets, on the west side of Brick Lane, were named Grey Eagle Street and Black Eagle Street. Thomas Bucknall, a London entrepreneur, is said by some to have built the Black Eagle brewhouse in about 1666, the year of the Great Fire of London, on land known as Lolsworth Field, Spittlehope belonging to Sir William Wheler. However, it remains unclear whether Bucknall actually was a brewer: the best that can be said is that on the land he leased “in 1681-2 the lay-out of buildings on this part of Brick Lane approximated to the present arrangement of brewery buildings round an entrance yard, and that this lay-out may date back to 1675.”

Joseph Truman is sometimes said to have acquired the brewery in 1679, from William Bucknall, going on to take out leases on neighbouring property. However, it is not until 1683 that Truman is found as a brewer in any records that survive today. He appeared that year in the register of St Dunstan’s, Stepney, on the birth of his daughter, as a “brewer of brick lane” [sic]. He became a freeman of the Brewers’ Company, the city’s guild of brewers, in 1690, five years after the guild had won a charter extending its control over brewers, like Truman, in London’s suburbs. The earliest known lease involving Truman is dated 1694, and refers to a brewhouse, granary and stable in the occupation of John Hinkwell (or Huckwell). With the premises came the use of two passages, one into Pelham (now Woodseer) Street, and one into Brick Lane, which indicates a site, confusingly, on the east of Brick Lane.

![Maps of Brick Lane, 1744 and 2013. Note the roads that have disappeared]()

Maps of Brick Lane, 1744 and 2013. Note the roads that disappeared into the growing brewery, Black Eagle Street and Monmouth Street, and how some streets changed their names while others to the north and west vanished with the arrival of the railway and Commercial Street in the 1840s. Double-click all pics to embiggen

Not until 1701 is Truman’s name known to be connected with the west side, when he obtained a sub-lease from Humphrey Neudick of a piece of land apparently to the north of Black Eagle Street upon which stood a dwelling-house and brewhouse. From this tangled narrative we can say that Joseph Truman was brewing in Brick Lane by 1683 at the latest, possibly on the east, Bethnal Green side, and had certainly acquired a lease on a brewery on the west, Spitalfields side of Brick Lane by 1701.

Who his partners were at this time is not known, but by 1716 they included his son Joseph II and Alud (or Alan) Denne, a publican. Another of Joseph Truman senior’s nine children, Benjamin, who was born in 1699 or 1700, became a partner in the brewery in 1722, the year after his father’s death in 1721. At this time there were four separate brewhouses on the site. They provided enough wealth for Joseph Truman II to retire to Trowbridge in 1730, and to be “reputed worth £10,000” (more than £20 million, in today’s terms) when he died in 1733, leaving behind only a daughter, Jane. (Jane Truman married William Butts, an apothecary from Derby, in 1742: one of her grandsons, Thomas Butts Aveling, born 1782, became head clerk at the Brick Lane brewery.)

What beers the Brick Lane concern was brewing when Benjamin Truman joined we don’t know either, but we can be pretty sure that one sort was dark brown, strong and well-hopped: the beer that eventually took the name porter, because of its popularity with the porters of London, the thousands of men who earned a living moving goods on and off ships moored in the river (the “Fellowship porters”) and around the city’s streets (the “Street” or “Ticket” porters, who also delivered parcels, letters and messages). Porter was developed around 1720 or so as an aged, hoppier version of the original London brown beer (the first known mention of porter by name comes from 1721), and it turned out to be the earliest beer suitable for mass production.

One of the necessities for making good porter was storing it in bulk for some months – as long as two years for stronger beer – to let it mature: at first it was stored in 108-gallon casks called butts, hence an alternative name for the brew, “entire butt beer”, but gradually the larger brewers began building bigger and bigger vats at their breweries to mature the beer. The best porter came from the biggest producers, who could afford the vessels to store the beer in and had the funds needed to tie up capital in maturing beer, a virtuous circle that meant the larger porter specialists began to pull away from their smaller rivals, especially those making the less popular, less hoppy brews. Eventually an aristocracy of half a dozen big porter brewers developed in London, supreme among 140 or so other much smaller concerns. Among those big porter specialists was Benjamin Truman.

In 1741 the brewery “rest book” (the end-of-year accounts) showed Brick Lane was making amber ale, three types of stout (brown stout, pale stout – stout originally meant any strong beer, not necessarily dark – and elder stout), and also “mild”. This last beer was not mild in the sense we know it today, but unaged porter, and it was already easily the most important beer produced. The brewery had getting on for 300 publicans on the books, though only 26 or so were tied houses actually owned by the brewery. The partners in the brewery were “the executors of A. Denne” with two 18ths, John Denne with six 18ths, Francis Cooper with three 18ths and Benjamin Truman with the remaining seven 18ths. A couple of years later, Truman’s share had risen to eleven 18ths, Cooper still had his three shares, and Ann Denne owned four shares.

![Sikr Benjamin Truman by Thomas Gainsborough]()

Sir Benjamin Truman by Thomas Gainsborough

In the 1740s Benjamin Truman, who had been living nearby in Princelet Street when his brother was in charge of the brewery, had built a big new house in Brick Lane in splendid Georgian style. But he had moved out of London by 1754, to a home near Hatfield, in Hertfordshire, just within commuting distance of the Black Eagle brewery along 18th century roads. In 1757 he confirmed his position as a country gentleman by taking over Pope’s Manor, a newly built house to the east of the Marquess of Salisbury’s Hatfield Park. Four years later, in 1761, the seal was almost literally put upon his arrival among the upper classes when he was “pricked” to become the High Sheriff of Hertfordshire.

As Sheriff, it was Truman’s job that year to deliver a loyal address from the county to the new King, George III. Truman had links with the royal family from many years before, in 1737, when Frederick, Prince of Wales, George III’s father, had thrown a public celebration outside his home, Carlton House, in London, for the birth of his daughter. The story that has come down is that the crowds had rioted over the quality of the four barrels of beer provided by the Prince’s regular household brewer. The next night the Prince repeated the public party, but Truman supplied the beer instead, to the satisfaction, it is said, of all.

According to the legend, George III was reminded of this incident 24 years earlier by Truman’s appearance at court with the address, and rewarded the Brick Lane brewer with a knighthood. The truth is that Truman’s elevation was more a reward for the large loans he made to the Crown to finance the country’s wars. The brewery had made Truman an extremely wealthy man: the “weekly money” he withdrew from the concern in the 1760s ran to almost £3,750 a year, the equivalent in earnings to more than £5 million today. His portrait, with a landscape in the background, was one of the largest Thomas Gainsborough ever painted.

All this wealth came from ever-increasing production of porter. Over the decades the paler beers had mostly disappeared from production at Brick Lane, with the books listing only mild porter, stale porter (that is to say, aged, or matured, not “off”) and brown stout, plus a little pale stout, probably for export. In 1748 the Black Eagle brewery was the third biggest brewery in London – and, probably, the world – with 39,400 barrels of beer produced in a year, behind only the two concerns owned by the Calvert family, the Hourglass Brewery in Upper Thames Street and the Peacock brewery in Whitecross Street, near the Barbican, both making 53,000 to 56,000 barrels a year. By 1760 Truman’s was still the third biggest of the London porter brewers, with just over 60,000 barrels a year, narrowly behind Samuel Whitbread in Chiswell Street (though still some way behind John Calvert’s Peacock brewery, on nearly 75,000 barrels a year).

![Frances Villebois by Thomas Gainsborough]()

Frances Villebois by Thomas Gainsborough

In 1776 the brewery had slipped to fourth place, though output was up again, at 83,000 barrels a year. Truman seems to have been pretty much running the business himself during this growth, though between 1767 and 1776 he had a partner called John Baker, with a one-third share in the business: presumably this was the successful Spitalfields weaver of the same name, who seems to have been Benjamin’s brother-in-law, having apparently married one of Joseph Truman I’s daughters.

By coincidence, Truman’s near neighbour in Hertfordshire was the brewer just ahead of him in porter production, Samuel Whitbread, who moved to Bedwell Park, Essendon, only a mile away from Pope’s Manor, in 1765. There is strong evidence that the two did not fraternise: Whitbread and his family were patrons of Essendon church, while Truman avoided that village, travelling past it from Pope’s Manor to worship at a church another couple of miles east in the village of Hertingfordbury. It was in Hertingfordbury churchyard that Benjamin’s only son, James, was buried in 1766, the same year as Benjamin’s wife Frances. Benjamin followed his wife and son into the grave in 1780, only three years after he had commissioned from Gainsborough four paintings, of himself, two granddaughters and two great-grandsons. (In the 1980s the tomb at Hertingfordbury was half-hidden under a yew, with the inscription barely readable, but the Truman arms – three hearts – could still be seen.) That year the Brick Lane premises were valued at £8,095 – around £70 million today, on a share-of-GDP basis.

Sir Benjamin Truman’s daughter, also called Frances, born 1726, had married a man called Henry Read, a landowner from Crowood, Ramsbury, Wiltshire, and given birth to two sons, William and Henry Truman Read, and three daughters, the eldest of whom, another Frances, had married her French dancing master, William Villebois. Neither William Read nor Henry Read were, apparently, interested in brewing, although Sir Benjamin assigned a one-eighteenth share in the Black Eagle brewery to William in 1775, and left a note in that year’s rest book that suggests William was expected to be working at the brewery in the future, if not working there already: in the note, Sir Benjamin emphasised to his grandson the need for hard work to ensure profits: “there can be no other way of raising a great Fortune but by carrying on an Extensive Trade. I must tell you Young Man, this is not to be obtained without Spirrit [sic] and great Application.”

![John Truman Villebois and his brother]()

John Truman Villebois and his brother, by Thomas Gainsborough

After Sir Benjamin’s death the business took William Truman Read’s name, becoming Read’s Brewery. But Sir Benjamin left the bulk of his estate, worth £330,000 (perhaps £460 million today), including most of the brewery business, to the sons of his eldest daughter, his young great-grandsons, John and William Truman Villebois. Sir Benjamin clearly hoped that these two, at least, would enter the family business, for his will gave instructions that the brewery house in Brick Lane should be kept in good condition until the two boys were 21, and he encouraged his granddaughter and her husband to live there: “it shall be a place of Residence for my said two Great Grandsons the Villebois as they are to be bred up to the Business conceiving it must be agreeable to Mr and Mrs Villebois to see how the Trade is going on which in a few years their said Sons are designed to have the benefit of …”

With William Read apparently uninterested in being a practising brewer, the management of the brewery stayed in the hands of Sir Benjamin’s head clerk, James Grant. In 1786 Read’s Brewery was the second-biggest producer in London, with just over 121,000 barrels brewed a year. This was only some 14,000 barrels behind Whitbread, but well ahead of the third-placed brewer, Thrale’s Anchor brewery in Southwark (soon to be renamed Barclay Perkins) at not quite 106,000 barrels a year.

Two years later, in 1788, James Grant bought William Truman Read’s one-eighteenth share in the brewery, Read apparently finally having given up any pretence of involvement in the business. Shortly after, however, on July 9 1789, Grant died at his country home, in Motcombe, Dorset. Within a few weeks, by August 26 1789, a 30-year-old Quaker businessman, Sampson Hanbury, had purchased Grant’s share and come to live in the brewer’s house.

Hanbury, whose family were originally from Monmouthshire, but whose grandfather had moved to London by 1724, setting up as a tobacco importer, was a member of an extensive network of Quaker merchants, bankers and brewers. His father, Osgood, was a banker in London, his mother Mary was the daughter of Sampson Lloyd of Birmingham, founder of what eventually became Lloyd’s bank; one uncle was David Barclay, the London banker who had led the purchase of Henry Thrale’s brewery in Southwark in 1781, turning it into Barclay Perkins (and who must have had discussions with his nephew about the wisdom of purchasing a rival London porter brewery); his wife, Agatha Gurney, one of the most beautiful women of the time, was from another old Quaker family with banking connections. Both Agatha’s father and brother were partners in Barclay’s Bank in London, and the clan also had a bank in Norwich, led by another of Sampson Hanbury’s uncles, John Gurney. This network was invaluable in helping the brewery’s finances, with Sampson Hanbury taking out regular loans from his relatives’ banks.

![Sampson Hanbury]()

Sampson Hanbury

While Hanbury ran the business, which changed its name to Truman and Hanbury, Sir Benjamin’s half-French Villebois great-grandsons remained majority owners but, despite their great-grandfather’s wishes, stayed strictly sleeping partners. Trade slipped badly at first, with the Brick Lane brewery falling to fifth place among the London brewers in 1792, selling only 98,000 barrels a year (Whitbread, for comparison, managed to produce more than 170,000 barrels). All the same, the business of a Truman’s pub at the time can be judged by an advertisement in The Times in January 1793 for the sale of the lease of the brewery tap house, the Black Eagle in Brick Lane, opposite the brewery. It was advertised as selling 14 butts of porter a month – 50 gallons a day – with “a considerable consumption for wine, brandy, compounds, &c” as well. As the century neared its end, in 1799, Hanbury had increased sales to 117,000 barrels a year, but Whitbread was still way ahead with more than 200,000 barrels and Barclay Perkins was making 136,000 barrels a year.

Steam power only seems to have arrived at Brick Lane in 1805, 20 years after most of the other big London porter brewers had taken up the new technology, when Hanbury ordered a beam engine from Boulton and Watt of Birmingham, at the same time building a new vat house. An earlier attempt to install a steam engine at the Black Eagle brewery, in 1788, had stalled when the partners failed to find room on the site for the engine house. Mechanical mashing only began in 1814, according to the Victorian journalist John Bickerdyke: before that date each mash was stirred the traditional way, using long oars or mash forks worked by “sturdy Irishmen”.

The year Brick Lane acquired its first steam engine, Hanbury had built his share up in the brewery from 1/18th to a third, after slowly buying more and more shares off the Truman Villebois brothers (two 18ths in 1799, for example), borrowing heavily from the brewery each time he purchased more shares, and paying the money back out of his share of the profits over the next year or two. Eventually, like Benjamin Truman, Hanbury amassed enough of a fortune to purchase a Hertfordshire estate, buying Poles, near Ware, and becoming Master of the local hunt, the Puckeridge Fox Hounds.

![Thomas Fowell Buxton]()

Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, 1st Baronet

In 1808 Hanbury’s nephew, Thomas Fowell Buxton, son of Thomas Fowell Buxton of Earl’s Colne, Essex, and Anna Hanbury, joined the brewery, aged 21 or 22. Buxton (who was not a Quaker, though his wife was) became a partner in 1811, at the age of 25, with a 1/12th share, bringing the last element to what would eventually, by 1827, be called Truman, Hanbury, Buxton and Company. By now the Black Eagle brewery was making 142,179 barrels of beer a year, some 20,000 barrels more than Whitbread, but a long way behind the number two London brewer, Meux Reid in Liquorpond Street, near Clerkenwell, on 220,000 barrels, and trailing Barclay Perkins in Southwark, on 264,405 barrels a year, by a large margin.

Buxton’s wife was one of the Gurneys of the Norwich bank, and a cousin of Sampson’s wife Agatha. A few years after he became a partner, in 1815, the shares in the brewery were redivided into 41 slices, and Buxton, evidently after bringing in some extra capital to the firm, increased his share to 8/41ths. His greatest gift to the brewery was sorting out the management of a concern that, by 1815, owned 200 pubs outright and financed another 300 landlords. But he also successfully intervened to prevent a disaster that might have destroyed the business.

The big London brewers had undoubtedly all been shaken by the disaster at Meux’s brewery just off Tottenham Court Road in 1814 when a giant vat containing 3,550 barrels of maturing porter burst, knocking down a wall and flooding out into the slums alongside, killing eight people. None of Truman’s vats seem to have been as big as that: the brewery gyle-book for 1812-1813 lists more than 60 vats, but the largest was only a little over 1,700 barrels, with the smallest 500 barrels. All the same, three years after the Meux tragedy, Buxton’s vigilance prevented a similar catastrophe at the Brick Lane brewery. In December 1817 he wrote in a letter to a friend:

“On Saturday last, in consequence of an almost obsolete promise to sleep in town when all the other partners were absent, I slept at Brick-lane. S. Hoare [a Quaker banker] has complained to me that several of our men were employed on the Sunday. To inquire into this, in the morning I went into the brewhouse, and was led to the examination of a vat containing 170 ton weight of beer [that is, about a thousand barrels]. I found it in what I considered a dangerous situation, and I intended to have it repaired the next morning. I did not anticipate any immediate danger, as it had stood so long. When I got to Wheeler-street chapel, I did as I usually do in cases of difficulty – I craved the direction of my heavenly Friend, who will give rest to the burthened, and instruction to the ignorant.

“From that moment I became very uneasy, and instead of proceeding to Hampstead [where he lived], as I had intended, I returned to Brick-lane. On examination, I saw, or thought I saw, a still further declension of the iron pillars which supported this immense weight; so I sent for a surveyor; but before he came I became apprehensive of immediate danger, and ordered the beer, though in a state of fermentation, to be let out. When he arrived, he gave it as his decided opinion that the vat was actually sinking, that it was not secure for five minutes, and that, if we had not emptied it, it would probably have fallen. Its fall would have knocked down our steam-engine, coppers, roof, with two great iron reservoirs full of water – in fact, the whole Brewery.”

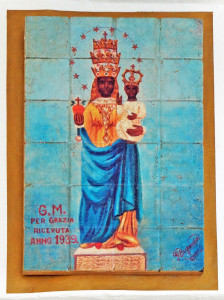

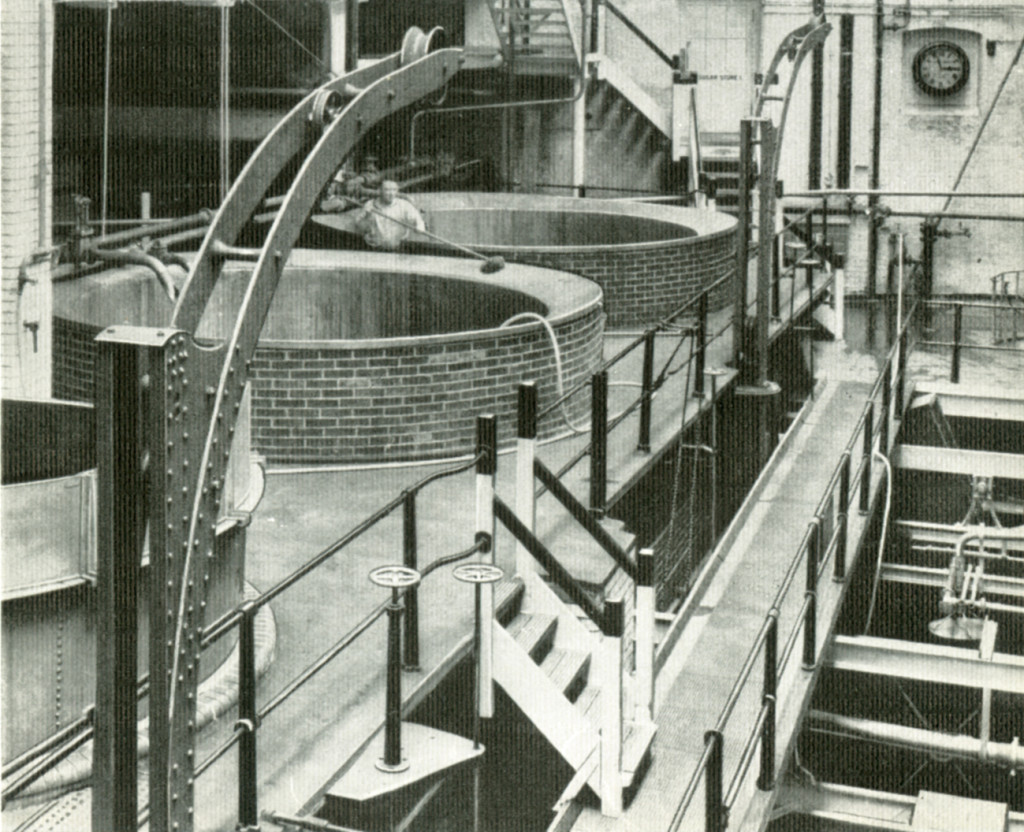

![Fermenting vats in the Brick Lane brewery]()

Fermenting vats in the Brick Lane brewery in the 1830s

The brewery had been surrounded by poor, overcrowded housing for many years, and soon after his arrival Buxton gave some of his energies to trying to improve the lives of the local people: he sought to give the labourers in the brewery an education, with the brewery’s partners providing a teacher (the brewery workers were encouraged to learn by Buxton telling them: “This day six weeks I shall discharge every man who cannot read and write”). He then widened his attention to the poor people living around the brewery itself. In 1816 he spoke at a meeting at the Mansion House in the City of London about conditions in Spitalfields, and raised £43,000 to aid the weavers who made up much of the population of the district, and who were close to starving because of a lack of work.

Huguenot silk weavers had begun settling in the area from the 1680s – there was a French chapel in Black Eagle Street in the 18th century – to be followed later by Irish weavers. In 1831 it was reckoned there were between 14,000 and 17,000 looms at work in Spitalfields, which had a population of about 100,000, half of whom were said to be “entirely dependent” on the weaving industry. But regular crises in the industry saw many of the residents mired in poverty, and throughout much of the 19th century Truman’s as a company was making frequent donations to charities set up to help the local poor: the Spitalfields Soup Society, for example, founded in 1797, which in just five months in 1826 gave away more than 66 tons of meat and 121,000 gallons of soup, and served nearly 14,000 people a day (and which was still in action more than 40 years later); and the Spitalfields Blanket Association, which provided hundreds of blankets every cold winter to those who could not afford bedclothes. The partners in the brewery supported the opening of a school in Spicer Street (now Buxton Street) in 1812, for children aged six to 16, with a fee per child of a penny a week; but even this sum was too much for many of the Spitalfields poor. Eventually the school closed, to be replaced in 1840 by All Saints’ National School, founded by Robert Hanbury, Sampson’s nephew, and linked to the newly built All Saints church, in Spicer Street. Truman’s also supported the vicar of All Saints, who was paid £50 a year to be the brewery chaplain as well.

Two years after the Mansion House speech, in 1818, Buxton was elected MP for Weymouth, aged 32. He was noticed by the great anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, MP for Hull, who asked Buxton to in 1821 to be his partner in the struggle to get slavery banned in Britain’s colonies. The Anti-Slavery Society was founded by Wilberforce, Buxton and others in 1823, but it was another 10 years of campaigning by Buxton and the abolitionists before an Act to abolish slavery was finally voted through in August 1833, with Emancipation Day a year after that. Buxton lost his parliamentary seat at the general election of 1837, but three years later he was created a baronet for his anti-slavery work. He died in 1845, and a statue in his honour was erected in Westminster Abbey, close to the memorial to Wilberforce. The cost of the statue was £1,500, of which £450 was donated by freed slaves in Africa and the West Indies.

![The plaque to Sir TF Buxton on the wall of the brewery in Brick Lane]()

The plaque to Sir TF Buxton on the wall of the brewery in Brick Lane

He was succeeded at the brewery by a younger son, also called Thomas Fowell Buxton. However, this Thomas, who lived, like Ben Truman, in East Hertfordshire, was an entirely different character from his father, if the comment of a man who had business dealings with him locally is to be believed: “As he is one of the richest men in the county, so he is the meanest. So thoroughly is he despised … not a village boy touches his hat when the wealthy brewer passes.”

Even before Buxton had become distracted by humanitarian issues, Truman’s had still felt the need in 1816 to strengthen its management, and its financial base, when the opportunity came to take on board as partners a couple of other Quaker brewers. Robert Pryor and his brother Thomas Marlborough Pryor were members of a family which ran a brewery and malting operation in Baldock, in Hertfordshire. But the two had been leasing another concern, Thomas Proctor’s brewery in Shoreditch High Street, just over a third of a mile from Brick Lane, which had ranked 23rd (out of more than 140) among the London brewers in 1792. One of the pubs the Pryors owned, and brought into the Truman’s estate was the Blue Last, Curtain Road, traditionally (although almost certainly wrongly) said to be the first pub to sell porter. (The rebuilt Blue Last is now in Great Eastern Street.)

When the Pryors’ lease on Proctor’s brewery ran out, the brothers brought to Truman’s their trade, worth 20,000 barrels a year, their capital, £47,350 (giving them three shares each in the Brick Lane brewery) and their own pubs, including the Blue Last. Sampson Hanbury thought it was an excellent deal, telling the Villebois brothers, whose agreement was needed to extend the partnership: “Our good friends and neighbours, Messrs Pryor … only wish to have as much profit of our trade, or a trifle more, as they can bring trade with them … they will add capital, more than equivalent which with truth I can say seems very advisable, if not necessary … We want capital and managers, I question if the whole trade could produce two persons who would unite so much of what we want – knowledge of the brewery in every part, economical habits, industry and respectability with money. Could you manage to come to town next week?”

The agreement was made, and for the next 138 years the brewery in Brick Lane was to be run exclusively by members of the Hanbury, Buxton and Pryor families. The immediate effect of the Pryors joining, however, was a big leap in production, to 185,412 barrels a year in 1818, putting the Black Eagle in second place among the big London porter brewers, though Barclay Perkins, then probably the biggest brewery in the world, was still far ahead, on 340,560 barrels a year.

In September 1819 the brewery was visited by the United States “Minister Plenipotentiary” (ambassador) to the United Kingdom, Richard Rush, who wrote in his memoirs:

“We were told that there had been brewed at the brewery last year two hundred and ten thousand barrels of beer, each containing thirty six gallons. The whole was performed by a steam engine equal to a twenty-six horse power. There were eighty vats and three boilers. We understood that the whole cost of the establishment, including the building, machinery, implements, horses and everything else, together with the capital necessary to put the brewery into operation, was upwards of £400,000. ‘And was this investment necessary before beginning the business?’, I asked. The answer was, yes, on the scale that I saw.

“The stable was scarcely the least curious part of the establishment. Ninety horses of the largest breed were employed, not as large as elephants, it is true, but making one think of them, and all as fat as possible. Their food was a peck and a half of oats a day, with mangers always kept full of clover, hay and cut straw, chopped up together with a machine, and hay in their racks throughout the night. It was among the largest breweries in London, but not the largest, Barclay’s, established by an American, taking the lead.”

Barclay’s huge dominance was not to last: a “splendid” new brewhouse was erected at Brick Lane around 1820 and by 1827, while Truman’s was selling 202,532 barrels of beer a year, Barclay Perkins was pushing out 276,000 barrels a year. To reward their head clerk, Thomas Butts Aveling, who had held that job for at least 20 years, for his role in the brewery’s increasing prosperity, the Black Eagle brewery partners gave him two of the now 47 shares in the brewery, the Villebois brothers giving up two of the 23 they still held. (Aveling, who was a great-grandson of Joseph Truman II via his mother, Frances Butts, had actually been allowed to be “interested in the profits and loss but not the capital” of the two shares since 1814. He and the Villebois brothers, of course, shared a great-great grandfather, Joseph Truman I.)

For more than a century, Black Eagle Street had been the thoroughfare on the southern edge of the brewery premises, running between Brick Lane and Grey Eagle Street, and then, as the brewery expanded, the thoroughfare through the middle of the brewery. But passers-by were increasingly having to dodge the brewery’s traffic: in October 1829 a complaint was made to the local magistrates that the brewery was placing its drays in Black Eagle Street by the side of the brewhouse “and suffering them to remain there until wanted for use, to the almost total destruction of the passage of the street.” Monmouth Street, which ran parallel between Grey Eagle Street and Brick Lane, had already been swallowed up by the brewery by 1826, but Black Eagle Street was not closed to the public until 1912/13, when it became the Dray Walk.

In July 1831 Brick Lane was the scene for what became known as “the Cabinet dinner”, when the Prime Minister, Lord Grey, and other members of the Government, including the Lord Chancellor, Lord Brougham, and seven other members of the House of Lords, visited the brewery for a tour and dined afterwards on beefsteaks “dressed at the stokehole” of one of the brewery furnaces. According to Truman’s own company history, Thomas Fowell Buxton had wanted to provide a banquet, but Lord Brougham (like Buxton, a passionate anti-slavery campaigner) had insisted that only steaks and porter would do. Among the guests at the dinner was the Spanish General Miguel de Álava, a good friend of the Duke of Wellington, and the only man to have been present at both the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of Waterloo.

The same year the partners in the brewery signed a further lease on the brewery land, for 61 years at £1,500 per annum and four kilderkins of the “Best Beer or Porter called Stout”. The brewery’s continued expansion was marked in November 1832 by the unveiling of a huge new circular fermentation tun with a capacity of 1,300 barrels, the first of four new tuns, and supposedly, according to a report in the Morning Advertiser, “the first of its size and shape ever to be constructed”. It stood on iron pillars 15 feet high, and its inauguration was celebrated by a luncheon for “the principal persons connected with the brewery” of 106 pounds of rump steak, once again “cooked at the stoke hole”, and “the best stout and ale which the establishment could furnish”.

Sampson Hanbury died childless in 1835. His heir was his nephew Robert Hanbury, who had joined the brewery in 1819 or 1820, aged around 23, and who inherited Sampson’s home at Poles in Ware. According to the Victoria County History of Middlesex, Robert Hanbury “possessed great business abilities,” and when Thomas Fowell Buxton’s parliamentary and campaigning duties “withdrew him from the active management of the brewery, the superintendence and control of the business passed entirely into [Robert Hanbury's] hands.” Robert Hanbury is also credited with starting ale brewing again at Brick Lane, “an example speedily followed by other London breweries”, as the capital’s drinkers tastes began to change in the 1820s and early 1830s to pale mild ale and away from aged porter: although ale had probably stopped being made at the brewery in the 18th century, it was certainly being brewed in 1804, but probably not in the huge quantities seen later. The “ale gyle” books at the Brick Lane brewery, the records of every brew of ale, begin abruptly in December 1831 (the gyle books for porter and stout survive from April 1802 onwards), and 1831 may well be when, at Robert Hanbury’s instigation, the brewery started providing ale to its customers again as well as porter and stout. The Topographical Dictionary of England said in 1833 that to the “very extensive Porter Brewery of Messers Truman, Hanbury and Buxton”, “a very considerable addition is at present being made for the purpose of brewing ale.” In 1840 the author Andrew Ure wrote that “the two greatest porter houses, Barclay Perkins & Co and Truman Hanbury & Co, have become extensive and successful brewers of mild ale, to please the changed palate of their customers.”

Thomas Marlborough Pryor, who had married Hannah Hoare in 1802, had died in 1821, aged just 44, at his home, Pryor House, Hampstead Heath. Thomas’s second son, Robert, who was born in 1812, worked as a banker, although he remained a partner in the Brick Lane brewery until the 1880s. Thomas’s brother Robert lived until his death in 1839, aged 60, in the house reserved for bachelor partners at the Brick Lane brewery. It was Robert the elder who put up the money in 1836 for one of his nephews, Alfred, to buy a brewery in Hatfield, Hertfordshire from (of all people, in light of later history) the brother-in-law of James Watney of the Stag brewery in Pimlico. (By another of those convoluted links so common in brewery history, a later partner in the Hatfield brewery, with Alfred Pryor’s son, was the son of the Reid of Watney, Combe and Reid.)

Around the same time, Truman’s had been employing a chemist, Robert Warington, born 1807, who joined the company in 1831, the earliest known appointment of a chemist in a British brewery, and stayed until 1839. Even so, although Warington used a microscope to study the brewery’s yeast, it would be another two decades before Louis Pasteur first accurately described yeast’s role in fermentation.

![The Brick Lane brewery 1842. Note the gentleman brewer at the brewery door in his apron, the draymen, and the railway bridge in the distance]()

The Brick Lane brewery 1842. Note the gentleman brewer at the brewery door in his apron, the draymen, and the railway bridge in the distance

Robert Pryor the elder introduced yet another nephew, Arthur Pryor, son of one of the Brick Lane brewery’s biggest malt suppliers, Vickris Pryor of Baldock, into the partnership in 1839. Arthur and his descendants were to play a dominant part in the brewery’s history. After his marriage Arthur Pryor lived in Down Lodge, Wandsworth, some seven miles from Brick Lane. In the 1850s, at least, every working day he would conduct family prayers at 7.45am for his children, their governess and the family’s 10 servants, before mounting his horse and riding to the local station. There he left the horse behind with a servant and caught the train to Brick Lane, returning home at 6pm.

Output at the brewery Arthur was helping to run was now a quarter ale rather than porter, and Brick Lane was challenging hard for the title of largest brewery in London, in the United Kingdom and, probably, the world. It looks as if the move into ale brewing instigated by Robert Hanbury rocketed Brick Lane into contention with its old rival Barclay Perkins in Southwark. In 1849-50 Barclay Perkins consumed 115,542 quarters of malt to make probably just over 330,000 barrels of ale and porter. Truman’s, meanwhile, consumed 105,022 quarters of malt to make only 30,000 barrels fewer. The whole operation now covered nearly six acres. The brewery used 130 horses that cost £70 each, managed by draymen earning the large sum of 45 shillings a week in the 1830s, to move the beer out to publicans, and consumed 500,000 barrels of water a year from its own 520-feet-deep artesian wells. It even had its own Thames-side wharf, Black Eagle Wharf, near St Katharine’s Dock, bought in 1841. Beer was being exported to the West Indies, North America and Australia.

Brick Lane was brewing nine different porters and stouts in 1850, including two different varieties of the standard mild (that is, unaged) “Runner” porter, one for town and one for country; “Keeping Porter”; Running Stout; Keeping Stout,; Double Stout and Imperial Stout (which had been around since at least 1847, when it sold for a price in bottle 75 per cent more than the ordinary porter). Research by Ron Pattinson has shown how the “runner” porter changed through the 19th century. In 1821 it was made from just under 78 per cent pale malt, and 22 per cent brown malt for colour and flavour, to give a beer around 6 per cent alcohol by volume from an original gravity of 1061, with three pounds of hops per barrel. But two years earlier Daniel Wheeler had invented highly roasted, deep black “patent” malt for colouring porters and stouts. This let brewers use more pale malt, which gave greater extract than brown malt, and was thus cheaper to use, and still get the same colour and much of the same flavour they did with a high proportion of brown malt.

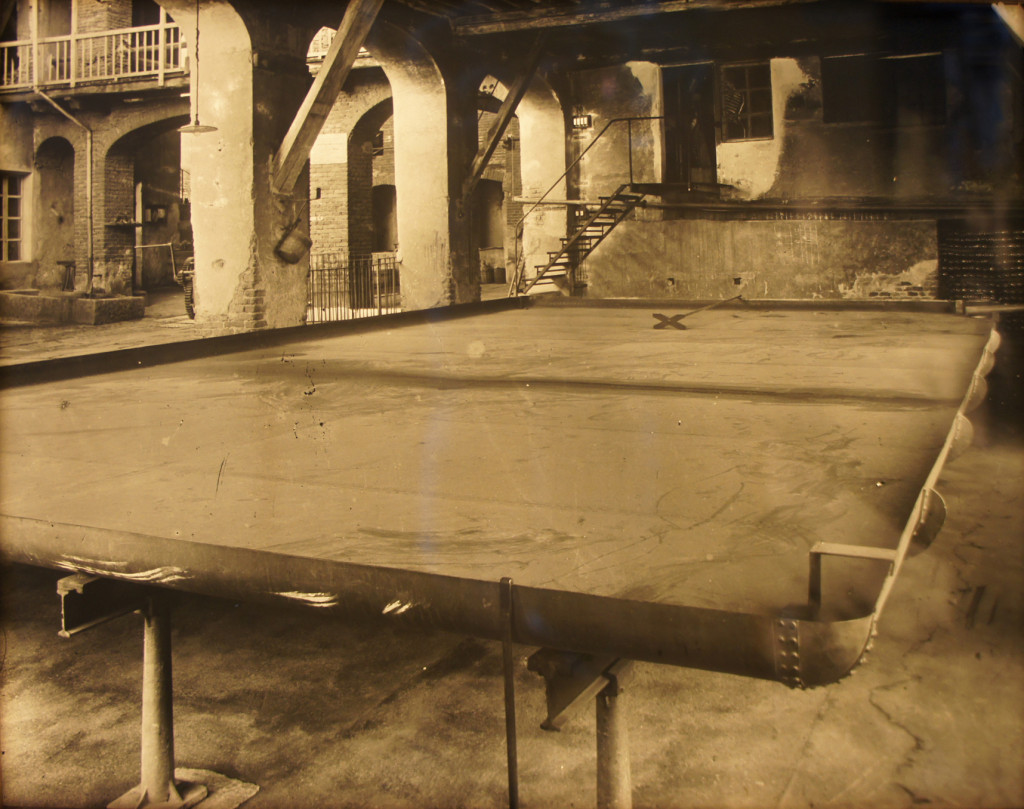

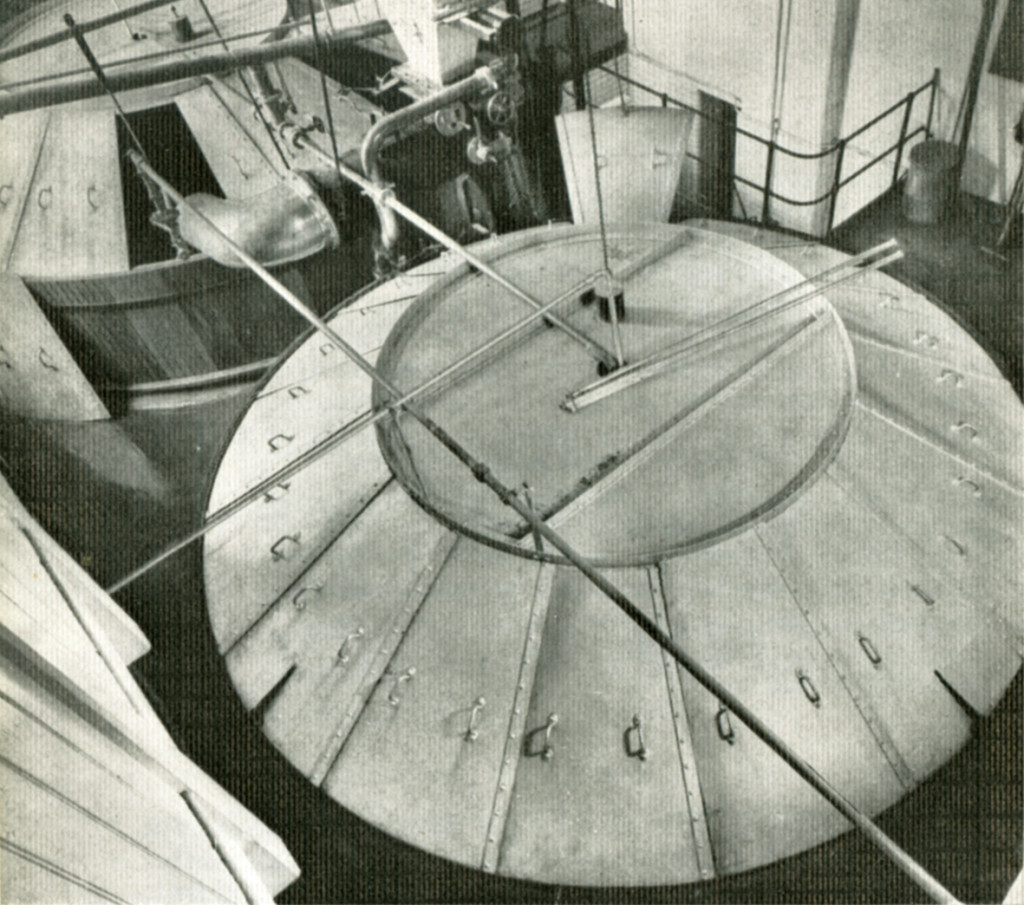

![Porter fermentation at Brick Lane]()

Porter fermentation at Brick Lane in 1889, with the pontos from where the excess yeast issued into a trough

By 1830 the Brick Lane brewery was using just under two per cent of patent malt in its running porter, only 11 per cent brown malt and almost 87 per cent pale malt. The amount of black malt rose to almost five per cent by 1870, though the brown malt proportion was up to almost 10 per cent. But as the popularity of porter dived, breweries started using cheaper ingredients, and in a later brew that same year the Brick Lane brewers used nearly 25 per cent sugar, with around five per cent each of black and brown malts, and only 66 per cent pale malt, plus 2.57 pounds of hops per barrel to give a beer with an OG of 1054 and an alcohol content of 5.7 per cent. It would probably have tasted noticeably different from the running porter of 50 years earlier: drier, less full in the mouth and quite likely less bitter, though roastier.

Fire was an ever-present danger at a brewery, and like many other breweries Truman’s had its own fire engines. They were in action in May 1841 when a “lucifer and congreve manufactury” (that is, a place making phosphorus matches – both “lucifer and “congreve” were names for matches in the 19th century) at the back of the brewery buildings on the east side of Brick Lane caught fire. Although the Truman’s fire engines were quickly on the spot, together with “a party of men in the service of the firm, who exerted themselves in a manner which called forth great admiration,” and despite the attendance of the parish fire brigade and fire engines from four nearby London Fire Engine Establishment stations as well, the entire building, just off Spicer Street – today’s Buxton Street – was burned to the ground in less than two hours. Happily, no one was killed, in what The Times revealed was the third destructive fire at a “lucifer manufactury” in a month. In 1848 a fire engine from Truman’s attended a blaze at a “wadding factory” in Spicer Street, for which the firemen were given a reward of 30 shillings by the Mile End and New Town parish authorities – money the firemen donated to the poor-box at the local magistrates’ court in Worship Street.

Like most London brewers, Truman’s had long bought much of its malt from Hertfordshire, where the maltsters specialised in the brown malts needed for porter. In Sir Ben Truman’s heyday, from 1746 to 1766, nearly 90 per cent of the brewery’s malt came from Hertfordshire, shipped down the Lea and other rivers and canals. In 1842 the Northern and Eastern Railway Company built a line from Hertford to London, and within eight years 57 per cent of Truman’s malt from Hertfordshire was coming by rail. In 1855 the brewery went over to bringing in all its Hertfordshire malt by rail. (East Anglian malt was shipped by barge from Colchester.) But Truman’s was sufficiently concerned about the monopoly power of the railways in 1873 to step in and buy the Stort Navigation, down which barges could bring malt from the town of Bishop’s Stortford, on the Herts-Essex border, to stop it falling into the hands of the railway companies, who might have closed down this rival means of transport for Truman’s essential supplies.

In 1853 Truman’s was using 140,090 quarters of malt a year to make 400,000 barrels of beer, now ahead of Barclay Perkins on 129,382 quarters a year, or around 370,000 barrels. The Brick Lane brewery had become the biggest in the world. Fraser’s Magazine visited the brewery in 1855, describing the equipment, which included two 800-barrel mash tuns, five coppers, each 300 to 400 barrels, the coolers at the top of the brewery where the boiled wort spread out in shallow vessels over an area of 32,000 square feet to cool down as rapidly as possible, and the four 1,400-barrel fermenting vessels. As the beer fermented it gave off “an immense quantity of carbonic acid gas” – carbon dioxide, which, being heavier than air, stayed close to the surface of the beer. “The men can detect the height to which it has risen within an inch or two with the bare hand, which immediately becomes sensible of the thick warm feel of this poisonous vapour.” Like other porter brewers, Truman’s let its beer undergo an initial fermentation for “two nights and a day” before running it off into rows of “rounds”, or pontos, to finish fermentation, with excess yeast pouring out into a wooden trough that ran between the rounds.

After fermentation was complete, the porter was run into the storage vats, 134 in number, holding a total of 100,000 barrels of beer. The malt bill for the previous year, Fraser’s Magazine revealed, was £400,000, with another £1.4 million for hops. The malt all looks to have come from Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex. The brewery owned 80,000 casks, each costing a guinea – £1 1s – when new, and kept in good order by 60 coopers. Other workers, from storehousemen to carpenters, wheelwrights to painters (who sent out 400 new brewery signboards in 1854, and refurbished another 350, at a cost of £1,300), totalled 219, including 40 bricklayers and 21 stablemen and farriers.

The full casks were taken out to pubs by dray, and Fraser’s Magazine rhapsodised about the men who delivered the beer: “The draymen of this establishment are eighty in number. Perhaps these brewers’ labourers are the most powerful body of men in existence. They are taller than the guardsmen, and heavier by a couple of stone. The dress of the drayman is peculiar: he wears a large loose smock frock extending to the knees, and over this a thick leathern kind of tippet, which covers the shoulders and comes down in front like an apron. The simple line of the costume makes the man appear still taller than he is. The size of these men is not owing to the unlimited beer which it is popularly supposed they have at command. They are all picked on account of their inches, and are limited to a certain amount of free stout every day. The extensive stock of horses kept here necessitates a of stable attendants: of these and there are twenty-one, so that the Messrs Hanbury & Co could, if they pleased, furnish a troop of the very heaviest cavalry at a moment’s notice.”

![GF Watts The Mid-day Rest]()

The Mid-day Rest by George Frederic Watts, featuring a Truman’s drayman

(It never seems to have supplied actual cavalry, but in 1859 the brewery agreed to pay the expenses of a rifle corps formed by its workers in response to the nation-wide Volunteer Force movement, which began that year. The brewery workers’ rifle corps seems to have eventually become part of the 1st battalion, Tower Hamlets Rifle Volunteers, of which Charles Buxton, third son of Sir Thomas, was the lieutenant-colonel in 1865.)

In 1865 a two-man commission from the Ale and Porter and Lager Beer Brewers of Philadelphia toured the brewery, on their way to Burton upon Trent and after having previously visited Dublin and Edinburgh, and been shown round Barclay Perkins and Whitbread. They found the only difference between Truman’s and its rivals was that many of its rounds, squares and pontoons were made, not of the usual wood, but slate, a material more usually associated with Yorkshire brewers. Truman’s had been using slate vessels “long enough to test their qualities, and are highly pleased with them on account of their cleanliness and durability,” the commissioners reported. (An article in the magazine Engineering in 1868 suggested that Barclay Perkins had installed slate vessels as well, but the idea does not seem to have spread far among London’s big brewers.)

On July 10 1866 the Brick Lane brewery was visited by the 25-year-old Prince of Wales, who was met by a delegation of three Hanburys, three Buxtons, one Pryor, the brewery manager, Alexander Fraser, and Henry Villebois, who still owned a substantial slice of the business, as the great-great grandson of Sir Benjamin Truman. The Prince of Wales’s own great-great grandfather, Frederick, Prince of Wales, of course, had been supplied with beer by Truman. Villebois was master of the West Norfolk Hunt, and his home, Marham House in Norfolk, was only eight miles from the Prince’s estate at Sandringham, which had been bought for him in 1862. He had become a good friend of the Prince through a mutual love of foxhunting, hounds and horses: it seems most likely it was Villebois who had invited Queen Victoria’s eldest son to the brewery. (Three of the brewery partners who met the Prince that day were Members of Parliament at the time: Robert Charles Hanbury, MP for Middlesex, Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, MP for Lyme Regis, and Charles Buxton, MP for Maidstone. Henry Villebois is sometimes said to have been MP for West Norfolk: he never was. His closest involvement in politics seems to have been that his sister Henrietta was, for a while in the 1830s, Benjamin Disraeli’s mistress.)

The Times report on the Prince’s visit dwelt with Victorian pride in the staggering statistics: 17,000 quarters of malt on the premises, about 2,500 tons, barely 10 per cent of the 174,674 quarters now used every year (suggesting an annual production of 500,000 barrels of beer), along with 900 tons of hops, again about a tenth of the total yearly requirement; 250,000 gallons of water used every day; five acres of cellars, with room for 100,000 barrels of beer. The brewery workers, in red stocking caps and white coats, showed off one huge porter vat in the cellar actually named the “Prince of Wales”, since it was finished and baptised the day the Prince was born, November 9 1841, and he was presented with a half-pint of Truman’s stout poured from a large silver jug. When he had drunk some he was cheered, literally, to the echo, as the hurrahs bounced down the vaults.

The Prince was also shown a dray being loaded with barrels using a hoist powered by a “gas engine”, an early form of internal combustion engine: alas, the report does not give the name of the manufacturer, but “Lenoir’s Patent Gas-Power Engine” was being advertised in The Times in 1864, suggesting that Truman’s may have been using one of the two-stroke engines powered by coal gas and patented by the Belgian engineer Étienne Lenoir in 1860. The Times report revealed that the brewery had nine steam engines and two gas engines in total, and used 9,000 tons of coal a year, as well as burning 8,000 to 9,000 tons of used hops to help power the boilers. All the furnaces for the steam engines had been fitted for the past 18 years with special “smoke-consuming” apparatus, to stop the surrounding district being covered with black soot.

Only 20 of the drayhorses were in the stables, the rest being out at work, but the Prince was shown a large painting by George Frederic Watts called “The Mid-day Rest”, featuring a Truman’s drayman, in red cap, with a couple of drayhorses, and he was also introduced to the drayman who had posed for the painting.

While the London porter brewers had coped fairly well with the rise in sales of mild ale, both they and the original mild ale brewers found themselves under pressure from the 1850s onwards from brewers in Burton-on-Trent, where the water was so much better for making the increasingly popular pale bitter ales, and where the two biggest brewers, Bass and Allsopp’s, were speedily outpacing the output of Brick Lane. By 1877 Bass was making a million barrels a year, wresting the crown of World’s Biggest Brewer from London, and the previous year Allsopp’s had hit a peak of 918,000 barrels.

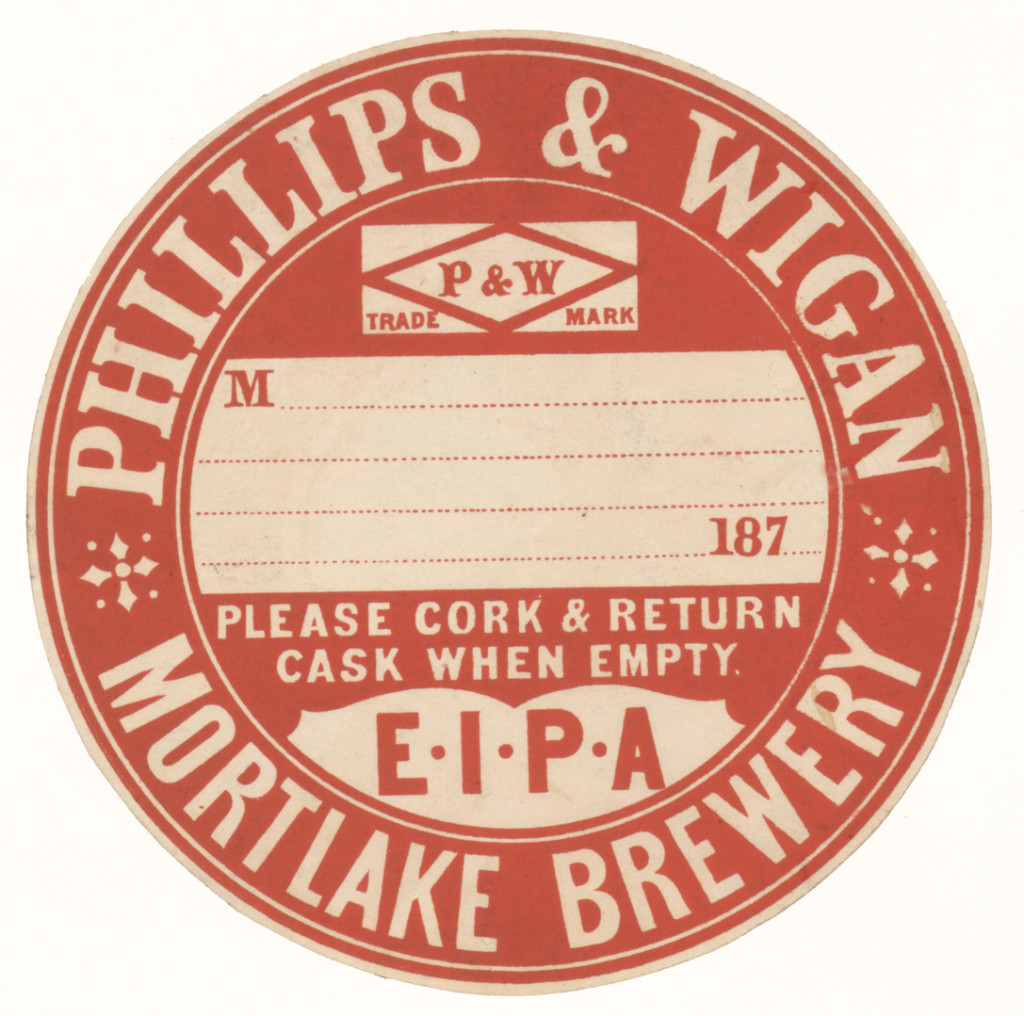

Truman’s decided that if it could not beat the Burton breweries, it would join them. After a couple of abortive attempts to set up agency agreements with Staffordshire brewers, in 1873 Truman’s bought the brewery in Derby Street, Burton, next to Burton Station, founded in 1865 by the Phillips brewery of Northampton. It was not a pioneer: Ind Coope, of Romford, Essex had acquired a brewery in Burton almost 20 years earlier, in 1856, apparently to supply the export trade, and the year before, 1872, an East End of London mild ale brewer, Charrington’s acquired a brewery in Abbey Street, Burton to make bitter beers. The following year, 1874, a third East End brewer, Mann Crossmann and Paulin, opened a branch in the Staffordshire town, building a completely new brewery in Shobnall Street, Burton (now owned by Marston’s).

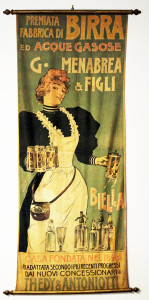

![Truman's Burton Brewery]()

The Black Eagle Brewery, Burton upon Trent, pictured in 1951

Arthur Vickris Pryor, son of Arthur Pryor, who had become a partner in the brewery in 1868, aged 22, was sent to Burton to run Truman’s new acquisition, and between 1874 and 1876 Truman’s enlarged and completely refitted the old Phillips brewery. The brewery gave Truman’s the advantage of being able to sell Burton pale ales under its own name, which is why so many ex-Truman’s pubs to this day still carry the phrase “London and Burton” carved into their fascias. Research by Ron Pattinson turned up the recipes for Truman’s two pale ales at the Burton brewery in 1877, both made with 100 per cent pale malt and hops from the United States and Sussex (English brewers were regular importers of American hops in the second half of the 19th century), with the P1 at an original gravity of 1066.5 and alcohol by volume of 6.6 per cent and the weaker P2 at 1062.3 OG and 5.7 abv. By the early 1880s, at the latest, Truman’s Burton brewery was also making the typical local range of Burton Ales, sweetish, fruity beers, made from pale malt (mostly around 96 per cent) and sugar, running from the super-strong No 1, which would later be called a barley wine, down to No 8, a 1054 OG mild. Burton Ale became a popular style in London, and most London brewers offered a Burton Ale right through to the 1950s at least, before they faded from the bar-top.

At first Truman’s Burton operation – which was also called the Black Eagle brewery – lost money, and the partners considered selling it. Eventually, by 1880, trade picked up and the first profit was shown. Still, the Burton brewery generally ran well below capacity, and London publicans never rated Truman’s Burton beers as highly as Bass or Allsopp, partly, it is said, because Truman’s often blended its Burton and London beers together, not always successfully. But in 1880 the company as a whole was making 580,000 barrels of beer a year, 100,000 barrels ahead of its nearest London rival, still Barclay Perkins, though still a long way behind both Bass and Allsopp’s in Burton and also, now, Guinness in Dublin, which was making more than 940,000 barrels a year, up from 350,000 barrels a year in 1868. (Guinness would hit 1.2 million barrels in 1886, seizing for itself the title of World’s Biggest Brewer.)

While the Burton brewery made pale bitter beers and Burton Ales, Brick Lane was still brewing considerable amounts of porter, but its biggest seller by now was X mild ale, a pale, unaged beer of the kind that was the standard public bar drink in London, selling for four (old) pence a quart. In 1880, X mild was 53 per cent of output at Brick Lane, made of 86 per cent pale malt and the rest sugar, its OG hovering around 1055 to 1056, lightly hopped compared to Burton bitter, at two pounds to the barrel, the alcohol by volume probably around 4.5 per cent, so likely a comparatively sweet beer. “Runner”, Truman’s “ordinary” mild (that is, unaged) porter, represented just under 25 per cent of output, “Running Stout” 10.6 per cent, Double Stout 5 per cent, Imperial Stout 2.5 per cent, and another five or so ales and beers the rest.

About the same time as it started its Burton venture, Truman’s was expanding its sales outside its London heartland. In 1879 it acquired a “large block” of public houses in Chatham, Kent. A year later a brewery stores was set up in Swansea, South Wales. Another agency was set up in Newcastle upon Tyne, where in 1897 Truman’s acquired a bottling business.

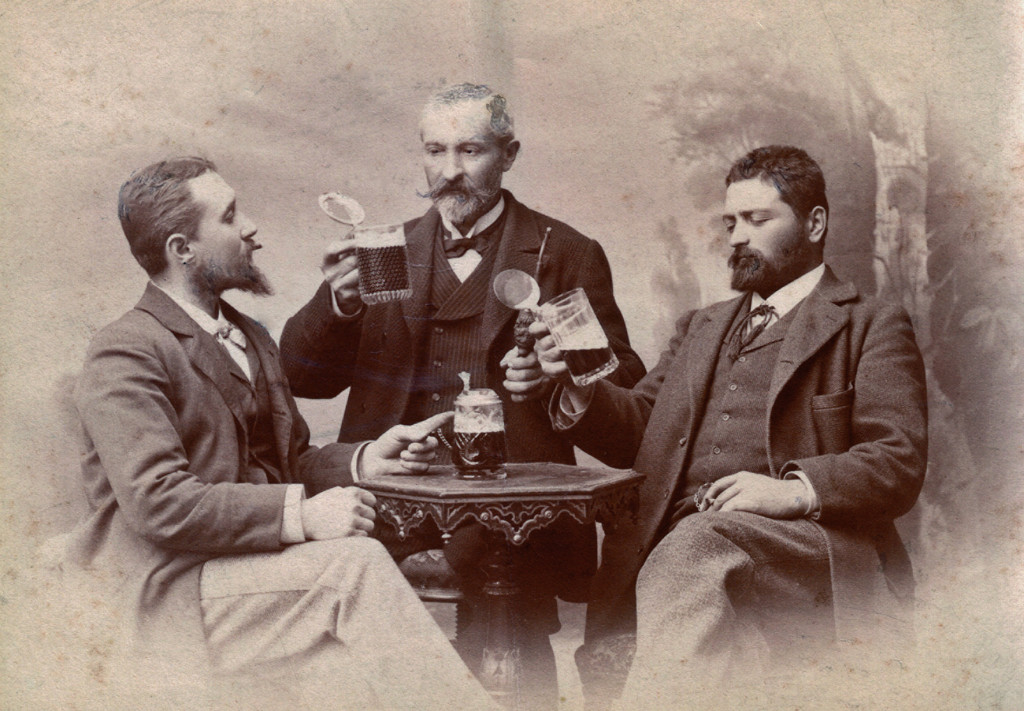

![1886 Truman's partners]()

Partners of Truman, Hanbury and Buxton 1886

1 Sir (Thomas) Fowell Buxton 3rd baronet 1837-1915, son of Sir Edward North Buxton, 2nd bart, grandson of 1st Sir TFB, MP for King’s Lynn 1865-68, Governor of South Australia 1895-1899, married to a daughter of the Earl of Gainsborough

2 John Henry Buxton 1849-1934, eldest son of TF Buxton, the 2nd son of Sir TF Buxton, 1st Bart

3 Arthur Pryor 1816-1904, 1st chairman of Ltd Co

4 Edward North Buxton (jnr) 1840-1924, 2nd son of Sir Edward North Buxton, MP for Walthamstow 1883-6, bought Hatfield Forest in Essex and donated it to National Trust

5 Arthur Vickris Pryor 1846-1927, eldest son of Arthur, married the Countess of Wilton in 1886 when he was 40 and she 50. Ran the Burton branch brewery

6 John Mackenzie Hanbury 1861-1923 2nd (& eldest surviving) son of Charles Addington Hanbury, and later chairman of the company.

7 Gerald Buxton 1862-1928, son of Edward North Buxton junior

8 Robert Pryor the elder, 1812-1889, second son of Thomas Marlborough Pryor

9 Charles Addington) Hanbury 1828-1900 or 1901 2nd son of Robert Hanbury, nephew of Sampson Hanbury

10 Thomas Fowell Buxton 1822-1908, son of Sir TFB 1st Bt,

11 Edmund Smith Hanbury, 1850-1913 son of Robert Culling Hanbury, former MP for Middx, 1823-1867, who was eldest son of Robert Hanbury, 1796-1884, nephew of Sampson Hanbury

12 Robert Pryor junior 1852-1905, 4th son of Arthur

Nine years earlier, in 1889, the partners in the brewery had finally taken the step of turning it into a limited company, Truman, Hanbury and Buxton Ltd. Other breweries had been turning themselves into limited companies since Guinness had raised millions in the first public float of a brewery three years before, but what may have pushed the Brick Lane partners into the move was the death in 1886 of Henry Villebois, last representative of the Truman family in the partnership. Villebois still had a 34 per cent stake in the business, and his surviving family wanted to take that money out. A grand £1,215,000 of ordinary share capital was issued, all of it taken up by the partners, with another £1.2 million in debenture shares. The first board of directors consisted entirely of Hanburys, Buxtons and Pryors, with Arthur Pryor, then 73, as first chairman. Pryor stayed in the chair until 1897, to be followed by Edward North Buxton, grandson of Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton. The share prospectus revealed that the brewery owned more than 300 pubs, leasehold and freehold.

The year Truman’s became a limited company, the journalist Alfred Barnard visited the brewery. He found work starting at 4am, as draymen loaded the drays and clerks and foremen supervised, “so that advantage may be taken of conveying the beer through the metropolis as early as possible before the traffic commences.” Barnard was hugely impressed with what he saw, proclaiming: “These London brewhouses exhibit a magnificence unspeakable … Entering the brewhouse from the courtyard we found ourselves on the floor of a most elegant and church-like structure, one of the largest of its kind in London. Looking up at the noble roof, and then right and left to the wide and spacious galleries by which it is surrounded, and the massive columns which support the various stages, on which are placed the numerous and gigantic vessels, we were struck by the beauty and utility.”

The company was still producing around 500,000 barrels of ale and porter a year, the second-largest quantity in London and the fourth-largest in the United Kingdom (which still included Dublin). It had dropped most of the strong, aged black beers: alongside the now dominant ales, the brewery made just “Runner” porter, “Country Runner”, Stout and Export Stou, with occasional brews of Imperial Stout.

![Ally Sloper 1908]() Around 1900 Truman’s moved up into Essex, buying the pubs belonging to a concern called Grimstones – evidently not a brewery – based in Colchester. However, the Brick Lane brewery by and large refused to take part in the rush of take-overs that was already halving and quartering the numbers of British breweries, preferring to rely on its reputation to sell its beer. A drawing by the famous Edwardian illustrator Will Owen, published in a magazine called Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday in 1908, underlines the brewery’s reputation for strong beer: it shows a Cockney called Bob slumped against a wall and declaring to his pal that he cannot get up because he is being held down by three men – “Truman, ’Anbury and Buxton!”

Around 1900 Truman’s moved up into Essex, buying the pubs belonging to a concern called Grimstones – evidently not a brewery – based in Colchester. However, the Brick Lane brewery by and large refused to take part in the rush of take-overs that was already halving and quartering the numbers of British breweries, preferring to rely on its reputation to sell its beer. A drawing by the famous Edwardian illustrator Will Owen, published in a magazine called Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday in 1908, underlines the brewery’s reputation for strong beer: it shows a Cockney called Bob slumped against a wall and declaring to his pal that he cannot get up because he is being held down by three men – “Truman, ’Anbury and Buxton!”

A few years earlier, in 1903, the brewery had taken on its first female employee, Miss G Key, something regarded as “a great innovation”. Spitalfields was still a violent district, and rather than let Miss Key walk to and from the station to work, Truman’s made sure she was carried in a brougham, a one-horse carriage named for the Lord Chancellor who had dined at the brewery just over 70 years before.

After the First World War Truman’s made its first London take-over, when it bought Michell and Aldous of the Kilburn brewery, Kilburn High Road in 1920. Six years later, in September 1926, Truman’s acquired the Swansea United Breweries and some 100-plus pubs, to add to the 21 pubs the Brick Lane brewery already controlled in Swansea. Swansea United was the result of an amalgamation in 1890 of Crowhurst’s Orange Street brewery and the Glamorgan brewery in the town, and its trademark was the White Horse. However, the purchase was not a huge success for Truman’s, and despite the fears of Welsh brewers it was not followed by a wave of other take-overs by English firms.

In 1923, on the death of the firm’s chairman, John Mackenzie Hanbury, his widow, Christine, was appointed to the board, the first female appointment to a position of power in the firm’s history. The main Brick Lane brewery underwent a rebuild in 1924, the same year Truman’s introduced a bottled brown ale for the first time, which was being sold under the name Trubrown by 1929. A price list from Christmas 1927 showed seven different bottled beers available “per large bottle” and “per flagon”: Dinner Ale, Eagle Pale Ale, Brown Ale, Oatmeal Stout, Eagle Stout, Special Stout and No 1 Burton barley wine, the last being sold in nips (6 2/3rd fluid ounces) only. The following year the Brick Lane brewery stopped brewing draught porter, after two centuries of supplying the beer to thirsty Londoners. An off-sales price list from the mid-1930s showed the company still making a London Double Stout and a Milk Stout, as well as Trubrown brown ale, Eagle pale ale and Sparkling Mild, while from the Burton brewery came No 6 Burton Mild Ale, a penny a pint bottle dearer than the London mild; Ben Truman Best Pale Ale; and, still, No 1 Burton barley wine.

![Brewery chimney, Brick Lane]()

Brewery chimney, Brick Lane

At the start of the 20th century, Truman’s still had 200 horses at Brick Lane for beer deliveries. The brewery was using steam drays by 1921 at least, and petrol drays from 1926. Gradually the number of horse-drawn drays decreased, releasing the land where the stables stood for a much-needed new boiler house. The old beam engine had been removed in 1896, and eight new boilers installed. These, too, were replaced in 1929, with a new boiler house on the other side of Brick Lane. At the same time the East End acquired another landmark, in the new 160-feet-high, 1,000-ton brick boiler house chimney, with the Truman’s name down the side. But Truman’s was still using drayhorses in the early 1950s, and in 1950 its Suffolk Punches won a prize at the Essex County Agricultural Show.

In 1930 Truman’s made another of its rare take-overs, buying Russell’s West Street brewery in Gravesend, Kent and its 223 tied houses. Russell’s, which dated back to at least 1834, when it was called Heathorn & Plane, had itself acquired four other breweries in North Kent and one in Essex. About the same time that it bought Russell’s, Truman’s seems to have acquired the six or so pubs around Bishop’s Stortford in Hertfordshire owned by the long-defunct Flinn’s brewery there. Brewing continued at Gravesend through until the 1960s.

Meanwhile up in Burton, Truman’s brewery was still busy, sending 90 per cent of its trade away by rail. Like the other Burton breweries, Truman’s had its own sidings, and even its own engines. (The Brick Lane brewery also had a siding, built after a special Act of Parliament in 1872, and in 1952 British Railways made for Truman’s a special bulk beer tanker for journeys between the two breweries.) The Burton brewery used the union system for brewing pale ale, although in 1934, at least, most of its mild beer was fermented in vessels fitted with skimmers.

The Brick Lane brewery came through the Second World War physically pretty unscathed, unlike some of its London rivals, such as Taylor Walker in Limehouse, which was forced to close for 18 months in 1941 after being hit by German incendiary bombs. But within a month of the war starting, on October 1 1939, the brewery had lost one of its directors, John “Jock” Hanbury, son of John M and Christine Hanbury, great-great-great nephew of Samuel Hanbury, who was a Pilot Officer with the RAF, killed aged 33 when his aircraft crashed in an accident while on duty. The sheer number of men called up caused problems: in April 1943 Truman’s was advertising for a “Chemist, wanted immediately, single-handed, for brewery laboratory.”

![Dray Walk Brick Lane 1951]()

Dray Walk, Brick Lane brewery, 1951, showing horse-drawn drays still being used alongside motorised ones

At the end of the Second World War Truman’s bought its own hop farm, and in 1947 it added its own maltings, at Long Melford in Suffolk. The first-ever non-family board member, Henry Mallen, who had joined the company as a boy in 1896, was appointed in 1954. The shock evidently spurred Truman’s, four years later, into another rare take-over, of Daniell and Sons Breweries Ltd in Colchester and West Bergholt, Essex and its 146 pubs. Brewing ceased at West Bergholt in January 1959 (it had stopped at the Castle Brewery, Colchester in 1892, five years after the two Daniell concerns had merged, though Colchester continued to be Daniell’s head office). But Truman’s kept a depot and regional offices at West Bergholt until 1986.

By the mid-1960s Truman’s had 1,300 pubs, concentrated mainly in the South East of England. It was losing some traditions: in 1967 the last apprentice cooper at the Brick Lane brewery passed out into a business where metal casks were steadily making coopers a rare species. The same year the last two dray horses, Suffolk Punches called Prince and Charlie, left Brick Lane for the West Bergholt depot.

The brewery was still a place where family members could find employment, and one was a young Francis Pryor, who joined Truman’s from university as a management trainee in 1967. Pryor, the great-great-great grandson of Thomas Marlborough Pryor, recalls that every morning the wind direction at the top of the brewery was recorded and the windows and roof vents were adjusted by the duty brewer to try to ensure that wild yeasts did not blow in from the nearby Spitalfields vegetable market. Francis did not continue his brewing career, however, going on to be an archaeologist, author, farmer, and one of the presenters of the Time Team programme on television.

Derek Prentice, now a brewer with Fuller, Smith & Turner in Chiswick, West London, also started his brewing career in the late 1960s at Truman’s in Brick Lane, and remembers that the Burton brewery, which was still going, would ship down three cask beers, called PA1, sold as Ben Truman, PA2, a “running” Burton pale ale, and, in the winter, an ale known simply as Burton, a darker 5 per cent beer “very akin to Young’s Winter Warmer, which was also originally known as Burton.”

The beers now brewed at Brick Lane included a pale ale sold as Eagle bitter with an original gravity of around 1036, a dark mild of around 1032 OG, a light mild called, internally at least, LK, for London Keeper, again around 1032 OG, and a stout called Eagle Stout with an OG of around 1040, the last survivor of a quarter of a millennium of porter and stout brewing at the Black Eagle brewery. The brewery also made a barley wine that consisted of a stock ale brewed in Burton and shipped down to London in cask at an original gravity of 1120 OG which was then blended with a “runner” beer brewed in Brick Lane at around 1065 OG. The blending rate “depended on final ABVs”, to give an alcohol by volume for the finished beer of about 8 to 9 per cent.

![Skimming the yeast from a fermenting vessel, Brick Lane brewery, early 1960s]()

Skimming the yeast from a fermenting vessel, Brick Lane brewery, early 1960s

Truman’s was still using the “double drop” method of fermentation, where the beer began fermenting in one vessel and then, after one or two days, was dropped into a shallower vessel on the floor below, to complete fermentation. The idea of the system was to leave behind the products of the “cold break”, proteins that had settled out as sediment, and aerate the wort. The vessels that received the still-fermenting wort at Truman’s were known as “cleanse batches”.

The 1960s were a time of huge upheaval for the British brewing industry: new national-sized giants, such as Allied Breweries and Charrington United, had grown up, as smaller family brewers succumbed to take-over offers. But in 1968 Truman’s chairman, Maurice Pryor, was declaring his company “fiercely independent”, even though ancient rival Whitbread, which had grown to become a national concern itself, swooping on family brewers all over the country, held a 10 per cent stake in the Brick Lane business.

The Truman’s board, at that time three Pryors, three Buxtons and a Buxton relative-by-marriage, responded to criticisms of the company’s then lower-than-average profits by appointing a 34-year-old management consultant, George Duncan, as a director in April 1968. It was quite likely Duncan who persuaded Truman’s in 1970 to sign an agreement with Tuborg to brew the Danish company’s lager at Brick Lane, and sell it in Truman’s pubs. The same year Truman’s dropped its last links with traditional cask beers, spending the large sum of £500,000 on new 100-litre metal kegs, and rebuilding its draught beer packaging lines.

Late in 1970 Truman’s announced the closure of the brewery in Burton upon Trent. Its 73 pubs around Burton, plus a depot in Warrington, were to be sold to Courage, another growing national brewer, in return for 36 pubs in London and £850,000 cash, making the deal worth a total of £2 million. At one point in the negotiations it looked as if Courage would take over the Burton brewery as well. But in the summer Courage had acquired John Smith’s in Tadcaster, giving it ample capacity in the North and Midlands.

![Truman's Best Stout label]() Maurice Pryor had died suddenly in December 1969, and the brewery was now being led by the outsider, George Duncan, who had become chief executive. Truman’s was being thoroughly shaken up, to give its shareholders (30 per cent of them institutions) a better return on their capital. Closing the Burton brewery had saved £500,000 a year, and the brewery in Brick Lane was being rebuilt, for £6 million, to improve costs (wastage from old, too large brewing vessels was estimated to be hitting Truman’s for £300,000 in extra Customs and Excise payments alone).

Maurice Pryor had died suddenly in December 1969, and the brewery was now being led by the outsider, George Duncan, who had become chief executive. Truman’s was being thoroughly shaken up, to give its shareholders (30 per cent of them institutions) a better return on their capital. Closing the Burton brewery had saved £500,000 a year, and the brewery in Brick Lane was being rebuilt, for £6 million, to improve costs (wastage from old, too large brewing vessels was estimated to be hitting Truman’s for £300,000 in extra Customs and Excise payments alone).

Duncan and his management team were openly admitting that profits from the Brick Lane brewery and its now 980 pubs (830 of them run by tenants) would not show a real turn-around from their level of £2.3 million pre-tax until 1972-3. Quite possibly it was this candour that led on July 1 1971 to a sudden and completely unexpected takeover bid for Truman’s from an outsider to the brewing business, Maxwell Joseph and his Grand Metropolitan pub and hotel chain. (The previous month Joseph had quietly asked Whitbread if it would sell him its 10.7 per cent stake in Truman’s, and had been rebuffed.)

Joseph, who obviously felt Truman’s and its pubs would fit in perfectly with his 250 Berni Inns and Chef and Brewer pubs, was offering £34 million, or 311.5p a share, well over their pre-bid price of 254p. If the bid was a surprise for Duncan and his chairman, Derrick Pease (a descendant of Edward North Buxton’s daughter-in-law’s family), it stunned another London brewer, Watney Mann (itself an amangamation in 1958 of what had once been the Pimlico porter brewery run by the Elliott family and the ale brewer Mann Crossmann & Paulin of the Mile End Road, Whitechapel). Over the preceding four months Watney’s had been quietly planning its own bid for the Brick Lane brewery.

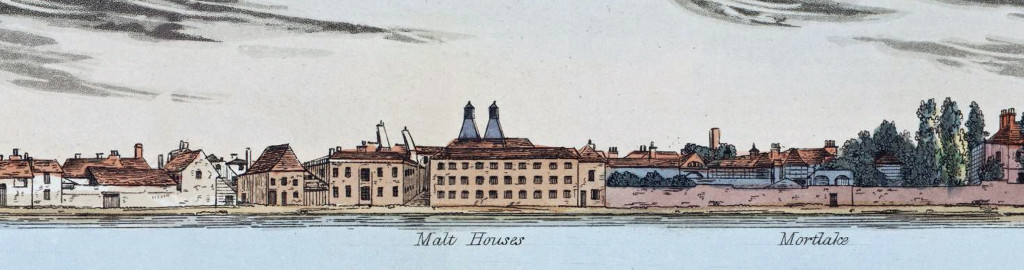

Watney’s, then Britain’s fifth-biggest brewer, had a problem. It wanted to close two of its high-cost breweries, the former Tamplin’s plant in Brighton and the Mann’s brewery in Whitechapel, and concentrate brewing at a rebuilt Mortlake Brewery by the Thames near Richmond. But Mortlake would not be ready until 1975, at a cost of £7 million. Michael Webster, chairman of Watney’s, had decided that Truman’s new plant, which had lots of capacity, could meet his company’s needs immediately, and save a great deal in running costs. Unfortunately for Webster, Joseph’s bid put a big foot in the middle of his preparations.

The first reaction from the brewing trade to the Grand Met bid was that someone, perhaps Whitbread, with its tithe of Truman’s shares, would rescue the Brick Lane brewery from the attempted embrace of the outsider Joseph. After all, the brewers had rallied together 12 years earlier when Sir Charles Clore had tried to take over Watney’s. There was also a certain amount of racism around in some quarters over the Joseph bid: the Daily Telegraph felt obliged to point out that no British brewery had ever fallen into Jewish hands.

However, Whitbread remained cool. It had decided that acquiring the Brick Lane brewery did not fit in with its own development plans. Instead Watney’s, galvanised by Joseph’s move, launched its own bid for Truman’s just over a week later, topping the Grand Met offer by £4 million. At the same time Watney’s bought almost a million shares in Truman’s on the stock market, taking its holding in the Brick Lane company to 18 per cent.

The Truman’s board, which itself controlled around ten per cent of the company’s equity, announced that it had accepted the Watney offer. But in fact the board had been completely split, with half voting for Grand Met and half for Watney Mann. The Truman’s ruling families were even divided among themselves. Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, the sixth baronet, was a Grand Met supporter, his cousins and fellow directors Henry and Mark Buxton voted for Watney. Only Derrick Pease’s casting vote as chairman had carried the day for the beerage against the outsider.

Joseph was far from quitting, however. Four days after the Watney bid, he raised his offer for Truman’s by more than a quarter, to £43 million. Within hours Watney Mann was back with a revised bid of its own, again topping Joseph by £4 million. What The Observer was to call “the most incredible take-over battle of all time” was under way.

![Royal Oak]() By now Whitbread had pledged its ten per cent stake to Grand Met, obviously feeling that it would rather not see Watney’s get any larger. But the Truman’s board was still divided between those who wanted the extra money being offered by the Red Barrel brewer and those who pointed out that a Watney take-over would mean 20 to 25 per cent redundancies at Brick Lane, with the loss of 800 jobs in one of the poorest parts of London. Amid rumours that several other big brewers were thinking of launching a bid for Grand Metropolitan itself, Truman’s workers voted in favour of the Joseph offer, and Watney’s announced it now owned between 22.5 and 25 per cent of the Brick Lane company. On July 20 1971, just under three weeks after Joseph made his first bid, the Truman’s board voted – unanimously this time – to accept the Grand Met revised offer.

By now Whitbread had pledged its ten per cent stake to Grand Met, obviously feeling that it would rather not see Watney’s get any larger. But the Truman’s board was still divided between those who wanted the extra money being offered by the Red Barrel brewer and those who pointed out that a Watney take-over would mean 20 to 25 per cent redundancies at Brick Lane, with the loss of 800 jobs in one of the poorest parts of London. Amid rumours that several other big brewers were thinking of launching a bid for Grand Metropolitan itself, Truman’s workers voted in favour of the Joseph offer, and Watney’s announced it now owned between 22.5 and 25 per cent of the Brick Lane company. On July 20 1971, just under three weeks after Joseph made his first bid, the Truman’s board voted – unanimously this time – to accept the Grand Met revised offer.

As is common in many take-over attempts, the offers from the two rivals were a combination of cash, and shares in the bidder’s own company. As the share prices of Grand Metropolitan and Watney Mann swayed up and down during the weeks, so the value of their two offers in real terms had altered. By July 29, with the fight still unresolved despite the Brick Lane board’s vote, the two offers were virtually equal, with Grand Met’s now worth £44 million and Watney’s £45 million. Watney’s felt compelled to put its offer up yet again, valuing it at £47 million. The Red Barrel men admitted their plans would involve 260 redundancies at Brick Lane, but said they could double output from Truman’s brewery within 12 months, and achieve savings of £1 million.

It took six days for Grand Met to come back with a revised offer, this time just £800,000 above Watney’s. In the meantime each side had been buying Truman’s shares on the stock market, with Grand Met happily paying almost £1.4 million to grab a block of 300,000 shares representing just 2.75 per cent of the total. By this point, five weeks after Joseph made his first bid, both sides owned about 30 per cent each of Truman’s. Grand Met still had the promise of the ten per cent controlled by the Truman’s board. But on August 14 Watney’s made another offer, this time valuing Truman’s at £49.5 million, close on half as much again as Grand Met had initially tried to pay.

This latest Watney offer again split the Truman’s board, which withdrew its recommendation of the Grand Met offer. Four of the Brick Lane brewery’s directors, led by Duncan, the chief executive, backed Watney’s. The other five, led by chairman Pease, supported Grand Met. The struggle had already bought a strike by Truman’s workers against the Watney bid. On Sunday August 16 it sparked a sermon in St Paul’s Cathedral from Canon John Collins, who attacked both bidders, saying they had no consideration of national interests, let alone Truman’s workers or the Brick Lane brewery’s many small shareholders.