You can hardly get fresher beer than from a bottle snatched off the production line by the managing director of the brewery, only seconds after it had been filled and capped – and, indeed, it’s excellent, cold, refreshingly flavourful and welcome, even at 10.30 in the morning. Mind, there are few or no Anglo-Saxon breweries where this would be possible, since health’n’safety barriers would be in place to prevent anyone from being able to reach across into the filling machinery and grab a passing bottle from the conveyor. However, this is Italy: while in a British brewery everybody would be forced into hi-vis jackets, ear protectors and goggles, here, where life is visibly more relaxed, visitors can wander about unworried by the HSE.

I am at Menabrea (pronounced roughly “MENahBRAYah”), one of the few surviving family-run Italian breweries, with roots that go back to before Italy was a single country. Menabrea is based in the town of Biella in Piedmont, 1,400 feet up in the foothills of the Alps, 40 miles from Turin to the south-west and 50 miles from Milan to the east. It is a town of 46,000 people, with soft water coming down from the Alps that, with plenty of nearby pastureland for sheep, has encouraged a local woollen industry: the town is home to Cerruti and Fila, among others. That same soft water is also very good for brewing lagers.

The brewery was started in 1846 by a couple of cafe owners, Antonio and Gian Battista Caraccio, and Antoine Welf, from Gressoney in the Aosta valley, to the north-west of Biella. Welf was a Walser, that is, a speaker of the Walliser dialect of German found in the Swiss canton of Valais and surrounding territories such as Aosta. Welf disappears, and in 1854 the Caraccio brothers started leasing the brewery in Biella to another Walser, Anton Zimmermann, also from Gressoney, and his compatriot Jean Joseph Menabreaz (sic), who were already running a brewery in the town of Aosta itself. Piedmont – and Aosta – were at that time part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, ruled by the House of Savoy, but in 1861, with some help from the French and Giuseppe Garibaldi, Victor Emmanuel, King of Sardinia, was able to declare himself King of a more-or-less united Italy. Three years later, in 1864, Zimmermann and Menabreaz – now, post-unification, with Italianised first names, Antonio and Giuseppe, and, in the latter’s case, a more Italian-looking surname as well, with the final “z” disappearing – bought the brewery in Biella from the Caraccios.

In 1872 Zimmermann left the Biella partnership to concentrate on the brewery in Aosta. However, he died the following year, and the Aosta brewery fell under the control of his nephew, Antonio Thedy. A couple of decades later, in 1896, Antonio Thedy’s brother, Emilio Thedy, who had married one of Giuseppe Menabrea’s granddaughters, was helping to run the Biella brewery, and it is Emilio’s descendant, Franco Thedy, who is now the MD there. Strangely, considering how many old-established Italian breweries have vanished, the Aosta brewery where Joseph/Giuseppe Menabrea started in the beer business is also still going, albeit on a different site, and is now one of four Italian brewing plants operated by Heineken, and producing Moretti, among other beer brands.

Menabrea itself ran into financial problems in the early 1990s, but in 1991 Paulo Thedy, Franco’s father, signed a deal which saw the company acquired another family brewer, Gruppo Birra Forst, founded in the South Tyrol village of Forst in 1857 (when the area was still part of Austria-Hungary: it passed to Italy after the First World War). The deal saw Menabrea keep a considerable degree of independence, with the Thedy family still in charge. Today production is around 180,000 hectolitres a year, 45 per cent bottled and 55 per cent keg, and 90 per cent sold in Italy – and of that, 50 per cent is sold in the north-west of the country, making Menabrea pretty much the Italian equivalent of a family-owned regional brewer.

The remaining 10 per cent is exported to 28 countries around the world. It is Franco Thedy’s ambition to grow that export figure that is the reason why I am in Biella, along with a bunch of style bloggers mostly about a third of my age, courtesy of Tennent’s the Glasgow-based brewer that is now importing Menabrea beers into the UK. Peroni, the SAB Miller-owned Italian beer brand, is massive – massive – in the UK, with sales in this country not far off ten times Menabrea’s entire output. Nobody at Tennent’s, or Menabrea, actually says so over the weekend I was in Piedmont with them, but clearly the thinking is that even a small slice of Peroni’s UK market would be very welcome for the Biella boys and girls. The company has already started to gain a small toehold: if you’ve been in the Zizzi pizza restaurant chain recently, you’ll have found Menabrea’s pale lager on sale.

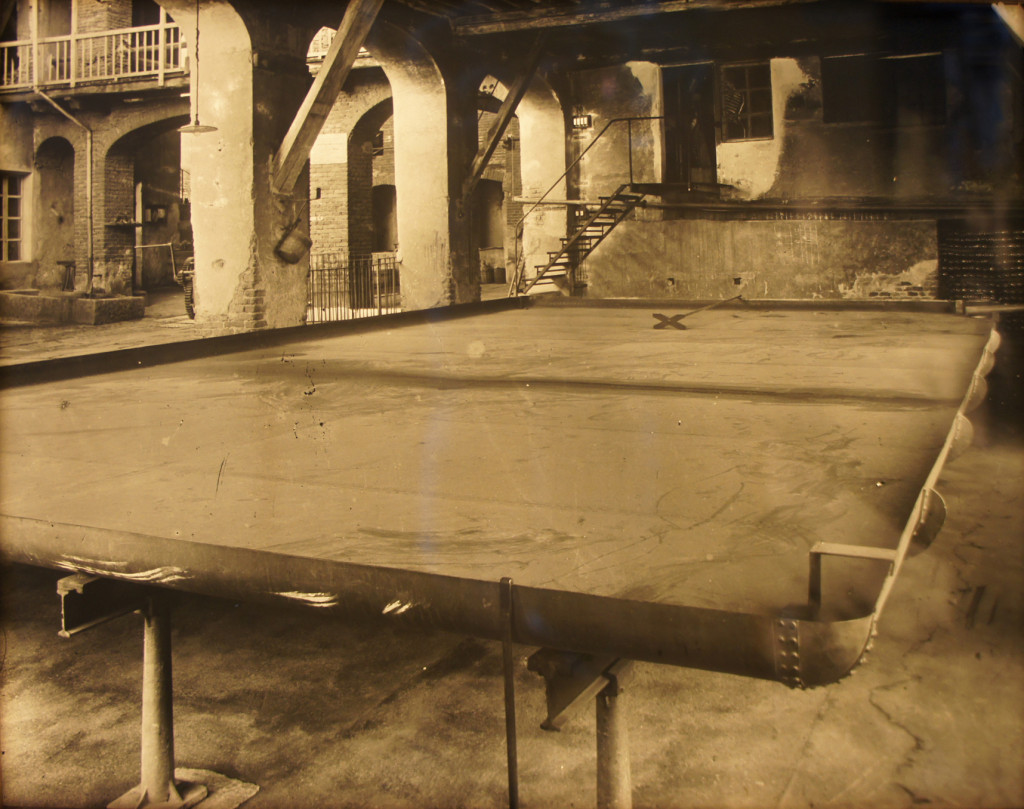

The brewery is on a 7,000 square metres (1.75 acre) site on the Via Ramella Germanin in the centre of the town, with some of the buildings dating back to the earliest years of the operation, including the circular former icehouse where ice was stored to enable the beer to be cold-lagered. The cramped site makes it difficult to expand, but Menabrea is now planning to build in 2016 a €2.5 million new modular brewhouse – the fourth on the site – with German kit that will take potential capacity up to 200,000 hectolitres. The current brewhouse, although put up only in 1986, “is at the end of its life”, Thedy admits: the equipment was second-hand when Menabrea acquired it, from what had been a test brewery for Heineken at one of its plants, and is now more than 40 years old, having been built in 1974. The new brewery will also give Menabrea the ability to produce more specialist beers, and seasonal brews – “It’s what the Italian market wants now”, Thedy says. Menabrea will not, however, he says, be producing the sort of wacky barrel-aged beers and so on that new Italian micros have been coming out with in the past few years: it sees itself as a brewer, not an experimenter. The latest expenditure comes after a €16 million spend over the past ten years to refurbish the plant, which includes €700,000 of German bottling equipment that flushes the oxygen from the bottles twice, to try to ensure there is as little oxygen inside the bottles to stale the beer as possible before they are capped.

The brewery is on a 7,000 square metres (1.75 acre) site on the Via Ramella Germanin in the centre of the town, with some of the buildings dating back to the earliest years of the operation, including the circular former icehouse where ice was stored to enable the beer to be cold-lagered. The cramped site makes it difficult to expand, but Menabrea is now planning to build in 2016 a €2.5 million new modular brewhouse – the fourth on the site – with German kit that will take potential capacity up to 200,000 hectolitres. The current brewhouse, although put up only in 1986, “is at the end of its life”, Thedy admits: the equipment was second-hand when Menabrea acquired it, from what had been a test brewery for Heineken at one of its plants, and is now more than 40 years old, having been built in 1974. The new brewery will also give Menabrea the ability to produce more specialist beers, and seasonal brews – “It’s what the Italian market wants now”, Thedy says. Menabrea will not, however, he says, be producing the sort of wacky barrel-aged beers and so on that new Italian micros have been coming out with in the past few years: it sees itself as a brewer, not an experimenter. The latest expenditure comes after a €16 million spend over the past ten years to refurbish the plant, which includes €700,000 of German bottling equipment that flushes the oxygen from the bottles twice, to try to ensure there is as little oxygen inside the bottles to stale the beer as possible before they are capped.

Factbox time: the brew length is 175 to 185 hectolitres – about 4,000 gallons, or 110 barrels. The beers are made with 73% malted barley from France and 27% maize, and, today, Danish yeast, though for a while the yeast was coming from the Carlsberg-Tetley operation in England, flown in to Milan airport, and soft water from the mountains that can be seen from the brewery. In the past the brewery made its beers from malt and rice, with the rice coming from the neighbouring Piedmontese province of Vercelli, famous for rice-growing. It started using maize 35 years ago, because it found that rice was too difficult to deal with in the brewery. The hops are pelleted Hallertau and Saaz. The main brews are the 4.8% abv “bionda” pale lager and a tasty 5% abv amber beer, with hints of chocolate and coffee, which is also being imported into the UK; three beers made under the “Top Restaurant” brands, including a pils and a bock, sold in Italy and the United States, but not in the UK; and a regular Christmas special. The brewery also produces a number of oddities besides its own beers, including all-malt “private label” beer for an Italian retailer, and also Allsopps Strong Lager, a 7.5% bottled beer brewed under licence from Carlsberg – today’s owned of the Allsopp name – for the Italian market, a last echo of the pioneering role Kirstie Allsopp’s ancestor’s played in introducing lager brewing to Britain.

The current fermentation cellars have 15 tanks, each holding 650 hectolitres, and all fermenting the beer at 14ºC for two weeks. Once fermentation is completed to the brewers’ satisfaction, the temperature is taken down to 0ºC and the yeast drops to the bottom of the fermentation vessels. The yeast is drained off to be reused, up to a maximum of seven or eight times, after which it is sold for pig food, and the fermented beer is run into vessels in the maturation cellar, where it is lagered for four weeks at the usual 0ºC. The company is building a new fermentation cellar with four new tanks to increase capacity, and also installing extra kegging capacity to give the brewery the ability to fill one-way kegs for the export market. It also fills 1,000 litre and 500-litre tanks for beer festivals and restaurants with unpasteurised, unfiltered beer, though currently only five retail outlets, one in Biella itself, the others in or near Milan, are being supplied with tank beer.

Most of the spent grain is sold to farmers as cattle feed, but some goes across the road to the Botalla cheese-making plant, where it goes into a “beer cheese” called Sbirro, which is also an Italian slang word for “cop”, policeman. The collaboration, Thedy says, came about 11 years ago when he and the owner of the cheese factory were having a 6pm beer together before going home. “I asked him, ‘hey, Andrea, how can we make a beer cheese?’, because when I went to Belgium I saw a lot of beer cheese. He said, ‘I’ve no idea, but we’ll try – why not?’ So we started the Menabrea beer cheese project. We were the first to produce a beer cheese in Italy, and now it’s a phenomenon, really popular.” The cheese is dropped into Menabrea’s “ambrata” amber beer, then covered on the outside with spent grain, which makes it look very different, and spends three months in the cellars of the cheese factory, maturing. A wholesaler is now selling the beer cheese in the UK, and if you see it, I can recommend it: a firm, tangy cheese with a hint of hops, good on its own and excellent melted on top of pizza.

Menabrea’s USP, Thedy believes, is the passion its people feel for the product. Modern craft brewers are using computers and automatic systems to make their beer, just like the really big breweries, Thedy says: “People are not really connected with the product.” At Menabrea, however, he insists, they are: the workers have been there for decades, with some retiring after 35 years at the brewery, and people whose fathers and grandfathers worked there. “Menabrea is one big family.” The people who work in the brewery, he says, “they are connected with the beer, they love this product. We want to keep the feeling, the passion, the tradition in this brewery. We want to sell our product, and our passion for the product, around the world. It’s not just beer – it’s a part of the Italian beer story.”

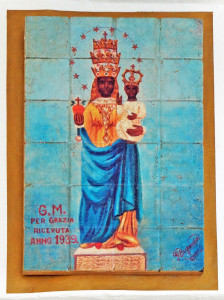

It was certainly fascinating, for me, to contrast and compare Menabrea with the Hook Norton brewery in Oxfordshire, which I went round last year: the two breweries are almost exactly the same age, both are still run by descendants of the founder, and the management of both breweries clearly have the same passion for the beers they produce, and the same urgent desire to see their companies survive and thrive. The kit is rather different, of course: Hook Norton is able to use equipment that is a century old or more, while the Biella operation’s brewing vessels are considerably newer, and much shinier. Both breweries, interestingly, have space devoted to artefacts from the past, though Menabrea’s is the more interesting simply because itr’s rearer, in my experience, to see items from an old lager brewery than stuff from an old ale brewery. Italy being Italy, the Menabrea brewery has a very good restaurant attached, in converted stables, which despite having easily 150-plus covers was packed out the night I and the style-bloggers threw ourselves at the typical Italian six-course blow-out: I’m not sure they’d be able to maintain that level of gastronomic intensity in the rural Cotswolds. Nor can I see any British brewery having anything like the picture of the Black Madonna of Oropa to be seen on one wall of the Menabrea brewery, a shrine marking the fact that the brewery was the first stop on the parading round the town of this ancient religious relic.

So: what chance for Menabrea in the UK market? I’d certainly like to see the ambrata widely available, there aren’t enough examples of that style of beer on sale here. Judging by my experience with the beer pulled right off the production line, the bionda will succeed if Tennent’s can crack one of the hardest problems facing any beer operator: logistics. I’ve increasingly grown to understand that the main problem with much of the lager sold in the UK isn’t that it’s not very good, but that it’s too old, and/or it’s been handled badly in the supply chain. This is true of many beers, but particularly so with lager: it really does need to be as fresh as possible.

And now, since while searching for background material for this post, I came up with a fair amount of information about the Biella brewery’s past, here is

A short history of Birra Menabrea

The roots of the current brewing operation in Biella lie 30 miles away, where Anton Zimmerman, a member of the German-speaking Walser community in Gressoney-Saint-Jean in the Aosta valley, born 1803, who had studied brewing in France and Germany, and Jean Joseph Menabreaz, also from Gressoney, started the Birra Zimmermann in Via Xavier de Maistre in Aosta itself in 1837, using barley grown largely in the nearby valley of Great St Bernard. According to one source, Menabreaz and Zimmermann were the first brewers in the Kingdom of Sardinia to use Bavarian-style bottom fermentation techniques. Meanwhile a third Walser from Gressoney, Antoine Welf, went into partnership in 1846 with two brothers, Antonio and Gian Battista Caraccio, cafe proprietors in Biella, to found a brewhouse there, taking advantage of the water that flows down from the nearby Oropa mountain. In 1854 the Caraccios, who were from from Bioglio, a village six miles north-east of Biella, began leasing the Biella brewery to Menabreaz and Zimmermann, who were presumably introduced to it through the Gressoney connection.

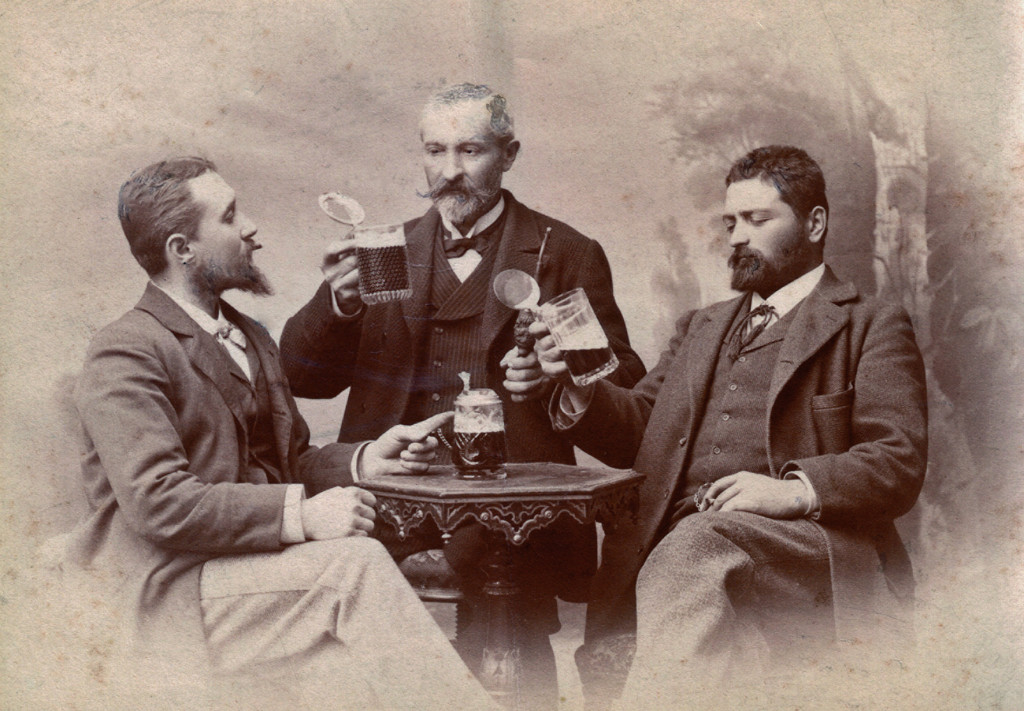

On October 3 1864 the brewery was bought by Menabreaz (now, since the unification of Italy, called Giuseppe Menabrea) and Zimmermann (now Antonio rather than Anton) for 95,000 lire, £3,800 in contemporary British currency, or about £330,000 in modern money. Three years later, on September 17 1867, a partnership agreement was drawn up which gave Zimmermann a 25 per cent share of the Biella brewery, Giuseppe Menabrea a 50 per cent share and two of Guiseppe’s sons, Francesco and Carlo, 25 per cent between them. In 1869 Giuseppe gave Francesco and Carlo another 12.5 per cent each, so that all four partners each now owned a quarter of the operation. Three years after that, Zimmermann, now in his 70s, evidently decided to concentrate on the Aosta operation, and on July 6 1872 a new company was formed to run the Biella brewery, G. Menabrea and Sons, the sons this time being Carlo, and Alberto, who was just 19.

Alberto died on August 5 1880, aged just 27, and just eight months later, on April 18 1881, Giuseppe Menabrea died as well. Carlo carried on with the business, forming another partnership with his brothers-in-law Antonio Mehr and Giuseppe Bieler to make beer and soda water and sell it “retail and wholesale”, paying himself and his partners a salary of two thousand lire a year. By 1882 the brewery was producing at least two types of lager, a blond Pilsner style and a dark version in the Munich dunkel style. The beers received praise that year from the Italian finance minister, Quintino Sella, who called it ” squisita”, and it may have been the minister’s praise that prompted the King of Italy, Umberto I, to make Carlo Menabrea a Knight of the Order of the Crown of Italy

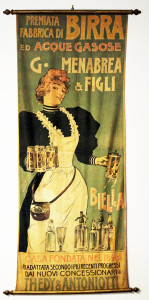

Three years on, in 1885, Carlo Menabrea also died, leaving his widow, Eugenia Squindo, a member of another Walser family originally from Gressone (and originally called Squindoz – like Joseph Menabreaz they lost the “z” to look more Italian), with three young daughters Albertina, Eugenia and Maria, aged 12, nine and seven. The widow Eugenia carried on with the brewery, helped by her brother Pietro Squindo, who ran an iron foundry in Biella. After her death, two of her sons-in-law, Emilio Thedy, a nephew of Antonio Zimmermann, who had married the young Eugenia, and Agostino Antoniotti, husband of Albertina, founded a partnership in 1896 to run the business. Among the changes they brought was the replacing of the brewery’s old wood and coal-fired coppers by modern copperrs heated by steam. Soon after, in 1899, the brewery won a silver medal at the Turin esposizione, followed by a Diploma of Honour and Cross in Dijon, and other prizes in Munich and Ghent, and then in 1900 a Grand Prix at the Paris World Exhibition, the first of a string of awards over the past century.

Three years on, in 1885, Carlo Menabrea also died, leaving his widow, Eugenia Squindo, a member of another Walser family originally from Gressone (and originally called Squindoz – like Joseph Menabreaz they lost the “z” to look more Italian), with three young daughters Albertina, Eugenia and Maria, aged 12, nine and seven. The widow Eugenia carried on with the brewery, helped by her brother Pietro Squindo, who ran an iron foundry in Biella. After her death, two of her sons-in-law, Emilio Thedy, a nephew of Antonio Zimmermann, who had married the young Eugenia, and Agostino Antoniotti, husband of Albertina, founded a partnership in 1896 to run the business. Among the changes they brought was the replacing of the brewery’s old wood and coal-fired coppers by modern copperrs heated by steam. Soon after, in 1899, the brewery won a silver medal at the Turin esposizione, followed by a Diploma of Honour and Cross in Dijon, and other prizes in Munich and Ghent, and then in 1900 a Grand Prix at the Paris World Exhibition, the first of a string of awards over the past century.

About this time the brewery had more than thirty employees, and production was about 8,000 to 10,000 hectolitres a year, hitting 10,814hl in 1910-11. About 90 per cent of production was of dark Munich-style lager, rather than the pale Pilsner kind.

About this time the brewery had more than thirty employees, and production was about 8,000 to 10,000 hectolitres a year, hitting 10,814hl in 1910-11. About 90 per cent of production was of dark Munich-style lager, rather than the pale Pilsner kind.

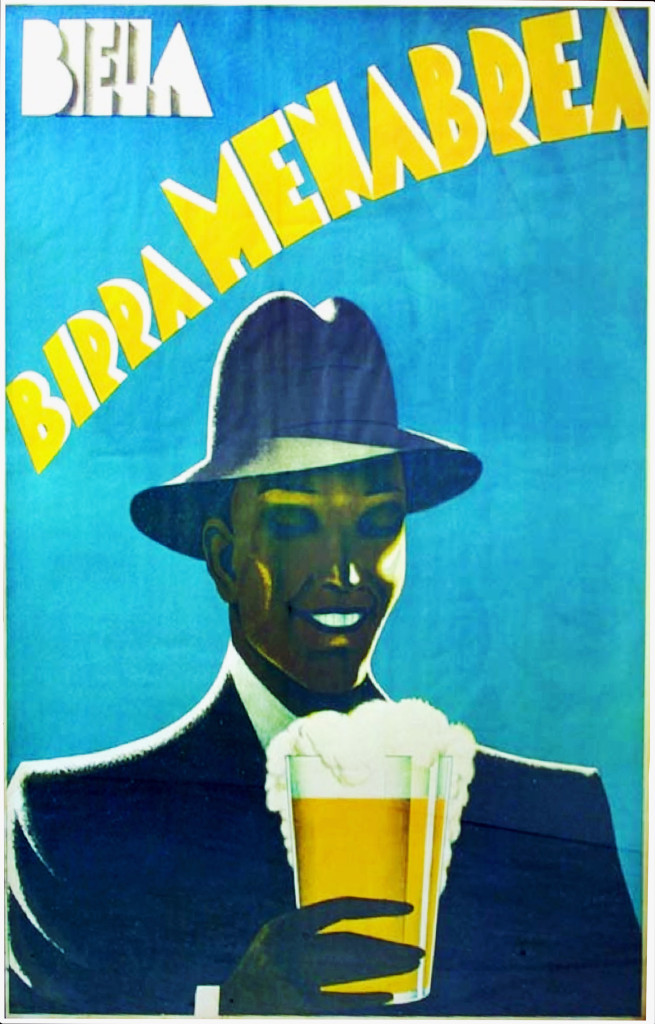

The brewery came through the First World War, though it lost the services of Federico, Emilio Thedy’s eldest son, who was called up to fight for his country. Production rose to 19,611 hectolitres in 1920-21. Under the Thedys, in 1930, Menabrea bought several “prestigious” taverns in the two biggest cities in Piedmont, Turin and Novara, to help advertise the brewery’s beers. It survived a period of high beer taxes in Italy in the 1930s, and the tumult of the Second World War, still with Emilio Thedy in charge, and when Emilio died in 1949 he was followed at the helm by the second of his five sons, Carlo.

By 1964 the brewery was still being run by Carlo Thedy, with the help of his nephew Paolo, son of his youngest brother, Franco. Eventually Paulo took over, and production crept up, passing 36,000 hectolitres and then 40,000 hectolitres in the 1980s. Menabrea had also begun importing beers from Britain and Germany, including John Bull Bitter. But financial worries caused Paolo Thedy to enter into a deal that saw the company become part of the South Tyrol-based family-controlled brewing operation Gruppo Forst, albeit with considerable autonomy and with the Thedy family still in charge. Thus when Paolo died in 2006, two years after production hit 100,000 hectolitres, he was followed as managing director by his son Franco, born in 1968.

Meanwhile in Aosta, Anton Zimmermann died in 1873, aged 70, and his nephew Antonio Thedy, one of six sons of Federico Thedy and Marta Zimmermann – whose younger brother Emilio, born 1876, was to marry Carlo Menabrea’s daughter Eugenia – took over. Thedy updated the brewery, and started the brewing of Munich and Pilsen-style lagers. Thedy’s daughter Matilde had married a man called Corrado Vincent, and in 1915, after Italy entered the First World War on the side of the Allies, the concern dropped the Germanic Zimmermann ( the name means “carpenter” in German) and became a limited partnership under the name Birra Aosta di Matilde Vincent e Compagnia, though with Thedy still in charge, since Corrado Vincent did not become the boss until 1925.

Meanwhile in Aosta, Anton Zimmermann died in 1873, aged 70, and his nephew Antonio Thedy, one of six sons of Federico Thedy and Marta Zimmermann – whose younger brother Emilio, born 1876, was to marry Carlo Menabrea’s daughter Eugenia – took over. Thedy updated the brewery, and started the brewing of Munich and Pilsen-style lagers. Thedy’s daughter Matilde had married a man called Corrado Vincent, and in 1915, after Italy entered the First World War on the side of the Allies, the concern dropped the Germanic Zimmermann ( the name means “carpenter” in German) and became a limited partnership under the name Birra Aosta di Matilde Vincent e Compagnia, though with Thedy still in charge, since Corrado Vincent did not become the boss until 1925.

Corrado’s and Matilde’s son Roberto Vincent took over, aged 20 in 1936, and pushed production up from just 2,600 hectolitres in 1931 to 7,000 hectolitres in 1955, despite having to serve in the Italian army during the Second World War. When Roberto Vincent died in 1965, aged just 51, after a serious illness, the company was sold, and in 1966 a new concern, Socièta Industrial Birraria, was set up to run the Aosta brewery. A new brewery was built in the nearby village of Pollein, and capacity eventually pushed up to 500,000 hectolitres.

SIB was bought by Henninger Brau of Frankfurt in 1973 and then sold to Dreher, owner of breweries in Trieste, Padua, Genoa and Turin (and controlled by Heineken since the early 1970s) in 1988. Plans were put in place to boost production to one million hectolitres, and the brewery is still running in 2015, one of four Heineken plants in Italy, producing brands including Moretti, Dreher, Prinz and Von Wunster, with an agreement signed earlier this year that it will continue in operation until at least 2026.